in 2013 i did 3 things i'm particularly proud of:

1. Problem Attic. i'd never done a real, honest-to-god project i felt proud of. finishing this lifted that weight off me. it also confirmed a lot of things i already knew. there were a lot of things that hurt me in the past year, and a lot of drama that caused ripples and split a lot of people i've been around apart. the time when i finished the initial version of PA felt like the epicenter of all of it. it's been really hard for me to deal with that feeling, like you have something you're trying so desperately to say but you're being ignored and swept under the rug by everyone around you because you're not as loud as them.

all this led me to feeling suicidal for maybe the first real time in my life. i guess the price you pay for doing things your way is feeling increasingly alienated from people around you. i spent several months being upset that many people i knew didn't even seem to want to go near my game, let alone entertain the idea that there might be something more there. the IndieCade rejection form was another blow, especially when a couple judges assumed i made the artistic choices i did in the game because i was inept. i'm also preparing for the inevitable disinterest from the IGF. i'll probably submit it to the Experimental Gameplay Workshop at GDC next year, if only because it's free, but i'm not hoping for much. and then i'll probably call the whole "attempting to get exposure for it" quits.

i've felt increasingly like everyone i know thinks i'm crazy and self-absorbed for harping on this game so much and just wants me to give it a rest. but i'm a stubborn person, and that deep stubbornness is what made that game, and is what motivates in general me to keep going and doing what i do. so that's what's i'm going to do.

i'm very proud to have made this game, and i think it's probably one of those things that will gain in reputation over time. i felt really overjoyed to see that there are some people (people i don't know at all, too!) who feel the same way. it makes me feel like i'm not so crazy for believing this after all. my dream is still to make it as an electronic musician, but maybe i'll keep trying to give this games thing more chances.

2. the three extended tracks i did on the MirrorMoon EP OST. i've struggled a lot with music for many years, and these have felt like by far the most cohesive things i've done in recent years. though if you want to give me money, you should do so on my bandcamp.

3. the two talks i gave: Re: Fuck Videogames and The Abstract And The Feminine. the former is a response to a bunch of different things going on in games around 2013, and i think more people need to read it if they can deal with eye-fucking and a few typos i'm too lazy to fix. the latter talks about a lot of issues surrounding gender (gender and art in particular) that a lot of people seem to ignore, so i think it's important to check out.

i'm not really a natural-born speaker and i still have a lot of dysphoria about my voice, so speaking at both conferences was a real challenge. at No Show in Boston, where i gave Re: Fuck Videogames, Courtney Stanton (the organizer) was nice enough to cover my flight and her and her husband Darius Kazemi were gracious hosts for someone like me who otherwise never would've been able to afford flying out to the east coast. unfortunately for the talk itself, i wrote everything in my talk out in article format, which makes for better reading than it did saying out loud. aside from that, i think No Show was an excellent and well run conference and i may attempt to submit a talk there next year .

my QGCon talk went a lot more smoothly, and i think i was able to convey all the thoughts i wanted to in the time allotted. i hope it came off for the people watching it. the conference itself i was happy to see exist, especially really close by, and meet some new faces. there were also several really good talks! but it also felt a little more jumbled and unfocused around several different ideas of what different people thought of as "queer", and some of the talks were basically just boring student dissertations (including a talk about Japanese representation of queer people in games that really bothered me and some other people). also, i hope they fix the audio on the stream next time around so people can actually hear most of the talks!

and of course, GDC and IndieCade were in 2013, both of which i have the benefit of being close to. both were, in themselves, a whirlwind of interesting people and experiences (IndieCade moreso than GDC), even if i feel less than enthusiastic about their overall aims as events, to put it lightly.

other notable things:

- i'm still broke as hell. if anyone likes my work and wants to give me money or help me find gigs doing music for games or whatever else, email or paypal me at liz dot ryerson at gmail or buy my stuff on bandcamp.

- you should play A.L.T., which is the best Doom mod i've ever played. also read my article about it on Unwinnable if you need convincing.

- a few articles i wrote on this blog ended up becoming pretty popular or whatever. i still like this one called "why should i love them?" the most.

- SCRAPS is an album of a lot of old kinda-embarrassing stuff of mine hopefully made less embarrassing by the super cryptic format

- i did the music and sound design for Crypt Worlds and Triad, which was fun.

- i got interviewed in RPS, which was pretty neat.

- i do plan on finishing my Doom videos eventually, but they're not a priority.

- speaking of that, apparently people kinda like it when you pretend to talk about whatever big current AAA game, even if what you're saying is not related at all.

- i wrote a couple more Wolfenstein 3d level design articles early this year, for anyone who might have missed them.

- i made Responsibilities w/Andi McClure at the very end of last year but you should still play it!

- i finally updated my website (ellaguro.com), which is still very much a WIP. i'm fond of the icons.

- i'm posting assorted other bits (like the glitch art stuff i've been doing the past couple days) on my tumblr, ellaguro.tumblr.com

Sunday, December 29, 2013

Monday, November 18, 2013

beyond "indie": a reprise

some two and a half years ago, Anna Anthropy wrote a post (and gave a micro-talk at GDC) titled "beyond indie". in it, she says:

"the indie label doesn’t contribute anything to the discussion except a needless sense of distance: calling a game an indie game or an author an indie developer just enforces the illusion that it’s an exclusive club, an inner circle to which most people aren’t admitted.

so my challenge to all of us is to stop thinking and talking in terms of indie games and indie developers, to get beyond the idea of an indie scene, to center the discussion on GAMES made by PEOPLE because there are going to be a whole lot more people making a whole lot more games and the indie label has become a moiety — a distinction we don’t need to make in an era where there’s no distinction between who can make videogames and who can’t."

there's still a lot of truth to Anna's words, but the usage of the term has also changed somewhat in the past couple years. the idea of "indie" implying a small handful of games made by an inner circle certainly very much applies to larger cultural representations like Indie Game: The Movie, or how a lot of the community around the IGF or IndieCade functions, but the label itself has also gained traction outside of those venues as a marketing term. most major games press has designated "indie" coverage now, and several "indie" games have gone on to be very successful in venues like Steam or The Humble Store. it's also the standard line parroted in the games press about next-gen consoles that Sony is "working with indies" in order to inject lifeblood into their current products, the PS4 and the Vita.

while the "indie" moniker has often been the subject of a lot of mockery (one example being the "Optimistic Indie" meme from 2011), it only seems to have gained greatly in usage and popularity since then. "indie games" now basically encompass anything and everything that isn't games made as part of the AAA development cycle. the popularity of things like Minecraft or Indie Game: The Movie means it's a moniker newer game developers readily desire to identify with because they want to be part of some scrappy cultural vanguard, either commercially or artistically (or both). but this also means that "indie" has become most readily identified with commercially successful developers working outside the AAA system, rather than the massive swath of interesting new games that have also been labeled "indie" but are seen as only as curiosities or failed experiments when evaluated on the terms of success dictated by the most culturally visible ones.

so while "indie" is still a derogatory term for a lot of self-identified "gamers" (search for "shitty indie game" on any major gaming website forum if you don't believe me), it's still very much growing as an established part of the industry. as if adding a nail in the coffin, a Sony spokesperson just this past week declared that "the Indie revolution is over" because Sony is now beginning to do what it needs to to adjust its old business models in order to more readily encompass indies as a viable part of the industry. Sony, of course, wouldn't have done this if they didn't see the writing on the wall. the industry has seen the success of "indie", in the midst of its own creative and financial stagnation, and is now readily attempting to co-opt it and pull it back into itself so that it can keep its machinery running.

but if the "indie revolution is over", what has been its lasting impact? has it been merely a way to inject lifeblood back into the industry by making smaller games more commercially viable, as Sony is trying to frame it? what about the legacy of the kinds of games that often appear on places like freeindiegam.es or forest ambassador? will they fall even further under the radar and have even less visibility once the industry fully co-opts "indie"?

i don't really know the answer to these questions. there at least seems to be more movement towards pushing beyond the idea of "indie" lately: there's Different Games, a conference run at NYU, that focuses on recognizing what we might think of as "unconventional" games, both digital and non-digital. as a name, i'm fond of "different games", if only as a meaningful but unspecific way to distinguish them from what normally gets labeled as a game, but it's lack of specificity means it's not particularly useful to be adapted as a widespread term. there's also the label "queer games", which was adapted to mean many different things by many of the speakers i saw at QGCon in Berkeley this past month. but "queer" obviously comes with a lot of baggage and implications as well. whatever the case, "indie" has proven itself to be an increasingly oppressive label that needs to be dropped.

the videogame industry is financially unstable and filled with deplorable labor practices and highly retrogressive values. becoming subsumed into the industry doesn't seem wise for either ideological or long-term financial reasons. i suggest we rescue what's worthwhile and get the hell out before the ship crashes and establish ourselves somewhere else. there are vast territories of the human experience that games can speak to, but these are rapidly narrowing with the widespread adaption of "indie" and all the implications that come with it. if we're at all concerned about the longevity of any of things done by game developers outside of the AAA system in the past five or so years, i believe we must drop any and all remaining identification with the label "indie" as soon as possible.

"the indie label doesn’t contribute anything to the discussion except a needless sense of distance: calling a game an indie game or an author an indie developer just enforces the illusion that it’s an exclusive club, an inner circle to which most people aren’t admitted.

so my challenge to all of us is to stop thinking and talking in terms of indie games and indie developers, to get beyond the idea of an indie scene, to center the discussion on GAMES made by PEOPLE because there are going to be a whole lot more people making a whole lot more games and the indie label has become a moiety — a distinction we don’t need to make in an era where there’s no distinction between who can make videogames and who can’t."

there's still a lot of truth to Anna's words, but the usage of the term has also changed somewhat in the past couple years. the idea of "indie" implying a small handful of games made by an inner circle certainly very much applies to larger cultural representations like Indie Game: The Movie, or how a lot of the community around the IGF or IndieCade functions, but the label itself has also gained traction outside of those venues as a marketing term. most major games press has designated "indie" coverage now, and several "indie" games have gone on to be very successful in venues like Steam or The Humble Store. it's also the standard line parroted in the games press about next-gen consoles that Sony is "working with indies" in order to inject lifeblood into their current products, the PS4 and the Vita.

while the "indie" moniker has often been the subject of a lot of mockery (one example being the "Optimistic Indie" meme from 2011), it only seems to have gained greatly in usage and popularity since then. "indie games" now basically encompass anything and everything that isn't games made as part of the AAA development cycle. the popularity of things like Minecraft or Indie Game: The Movie means it's a moniker newer game developers readily desire to identify with because they want to be part of some scrappy cultural vanguard, either commercially or artistically (or both). but this also means that "indie" has become most readily identified with commercially successful developers working outside the AAA system, rather than the massive swath of interesting new games that have also been labeled "indie" but are seen as only as curiosities or failed experiments when evaluated on the terms of success dictated by the most culturally visible ones.

so while "indie" is still a derogatory term for a lot of self-identified "gamers" (search for "shitty indie game" on any major gaming website forum if you don't believe me), it's still very much growing as an established part of the industry. as if adding a nail in the coffin, a Sony spokesperson just this past week declared that "the Indie revolution is over" because Sony is now beginning to do what it needs to to adjust its old business models in order to more readily encompass indies as a viable part of the industry. Sony, of course, wouldn't have done this if they didn't see the writing on the wall. the industry has seen the success of "indie", in the midst of its own creative and financial stagnation, and is now readily attempting to co-opt it and pull it back into itself so that it can keep its machinery running.

but if the "indie revolution is over", what has been its lasting impact? has it been merely a way to inject lifeblood back into the industry by making smaller games more commercially viable, as Sony is trying to frame it? what about the legacy of the kinds of games that often appear on places like freeindiegam.es or forest ambassador? will they fall even further under the radar and have even less visibility once the industry fully co-opts "indie"?

i don't really know the answer to these questions. there at least seems to be more movement towards pushing beyond the idea of "indie" lately: there's Different Games, a conference run at NYU, that focuses on recognizing what we might think of as "unconventional" games, both digital and non-digital. as a name, i'm fond of "different games", if only as a meaningful but unspecific way to distinguish them from what normally gets labeled as a game, but it's lack of specificity means it's not particularly useful to be adapted as a widespread term. there's also the label "queer games", which was adapted to mean many different things by many of the speakers i saw at QGCon in Berkeley this past month. but "queer" obviously comes with a lot of baggage and implications as well. whatever the case, "indie" has proven itself to be an increasingly oppressive label that needs to be dropped.

the videogame industry is financially unstable and filled with deplorable labor practices and highly retrogressive values. becoming subsumed into the industry doesn't seem wise for either ideological or long-term financial reasons. i suggest we rescue what's worthwhile and get the hell out before the ship crashes and establish ourselves somewhere else. there are vast territories of the human experience that games can speak to, but these are rapidly narrowing with the widespread adaption of "indie" and all the implications that come with it. if we're at all concerned about the longevity of any of things done by game developers outside of the AAA system in the past five or so years, i believe we must drop any and all remaining identification with the label "indie" as soon as possible.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

my QGCon talk - "The Abstract and the Feminine"

========================================

before i begin, i want to make this clear: these are two problematic terms. i chose a slightly provocative title for a queer conference because "queer" itself, despite being a very inclusive term in a lot of ways, comes with a lot of implications and baggage for a lot of different people. the label tends to embody a more western, white, urban, educated sensibility. but i want to be clear: femininity and masculinity are abstract concepts as they exist in our culture. it is not my intention to back any prescriptive definitions about gender norms or behavior. at heart i think they are really a pieced together assemblages of ideas into oppressive archetypes, and what gender or identity you assign them to really doesn't matter.

in the same way, i say "abstract" to mean an idea that exists in our culture of something that is more ephemeral, and not representational way we think about representation. we might see the abstract as frivolous, or incomprehensible, or messy, or incomplete. but "abstract" is a term that could be applied in many ways to mean many different things. so it's important to recognize that these terms are constructions, and ones with much of the language of oppression built into them.

so yes, these issues are hard to talk about with correct terms, but in itself the idea of an inherent correctness or consistency to a set terms we can use and all know what it means is part of the problem. the more weight you place into a concept the more it begins to crumble. the more you look into this issue, the farther things spiral down into a wormhole.

====

Erin Stephens-North talks about this issue as a divide between "maleness" and "femaleness" is in her excellent essay gender and brilliance:

maleness enables “the explicit.” it is also a culture, a culture of the illuminated, the visible. maleness manifests in “seeing,” “naming” and “doing,” as these words are commonly understood. it is the means by which anything is done—the means by which a thought is thought, a piece is crafted, a scene is surveyed. it is language. it is whatever is acknowledged as common currency amongst human beings. maleness asks: “so what are you saying?” or “so what do you do with this?”

femaleness is the reason for the doing. femaleness is reality. femaleness is anything that must be believed in before it is seen. it cannot and will not speak. it learns and speaks of itself only through maleness. it is the expanse of infinite possibility. it has no nature.

to be male is to be “consistent.” to be female is to appear to be inconsistent.

the vast majority of female brilliance is lost (or is invisible), not because brilliant female-thinking people do not attempt to communicate what they see through various forms of expression, nor for the reason that they do not understand the principles of logic, aesthetic consistency or craftsmanship, but because they encounter the obstacles to communication associated with femaleness.

==============

there's that saying: if you ever see someone credited as Anonymous in history, they're almost always female.

on its face art could be the embodiment of this female idea, but in actuality the art that's been made - and the way we think about and talk about that art has really been defined by this "maleness" way of thinking to idealize and imprison and co-opt and use the "femininity" and "abstract"-ness to its own ends, just as the rest of the Western world has been.

and i think these ideas end up culturally inherently circling back down to this archetypal, cultural idea of "masculinity" vs. "femininity" at their core.

if we look at different media, especially at the inception of this media, or the beginning of movements within it, we see the presence of women whitewashed over and made invisible. you see this visually represented in this cartoon about the state of comics by sloane i took from twitter a few days ago.

there's something about newness in itself that embodies this "feminine" or "mysterious" ideal.

look at the situation at the inception of film: “during the teens, 1920s, and early 1930s, almost one quarter of the screenwriters in Hollywood were women. Half of all the films copyrighted between 1911 and 1925 were written by women.” we all know what happened afterwards.

in visual art, earlier i was embarrassed did not know a single visual artist who i could name as a favorite who was female. so i started searching for stuff online - and i eventually found quite a few artists by resorting to clicking on random people from the list of "female visual artists" an wikipedia, and a lot of interesting stuff came up - but basically none of it i'd ever heard of. like Jacquine Lamba (who is apparently most well known for having sex with Fridha Kahlo by the way). a lot of her early work is lost. i can't even find a bigger version of this excellent-looking painting anywhere online. i'm almost positive if she was male this would not be the case.

one of the most haunting things for me is an interview with Nico, towards the end of her life. the interviewer asked her if she have any regrets about her career. she said she regretted that she was never born a man.

in, electronic music (a subject dear to me), women played a vital role as pioneers. three well known examples are

delia derbyshire

wendy carlos

laurie anderson

but then here a quote from one of the most well-known and well-respected electronic musicians of any gender in 2008:

"it feel(s) like still today after all these years people cannot imagine that woman can write, arrange or produce electronic music. i have had this experience many many times that the work i do on the computer gets credited to whatever male was in 10 meter radius during the job. people seem to accept that women can sing and play whatever instrument they are seen playing but they cannot program, arrange, produce, edit or write electronic music."

spoiler alert: it was this lady.

===============================

okay, so i wanted to look at a bit of a talk about the two hemispheres of the brain from iain macgilchrist, who is a neuroscientist and psychiatrist. i'm gonna gloss over a lot of the talk about the differences between the two hemispheres so you can get the important bits of it.

(i'm just going to link to the whole talk on youtube here).

=================================

the thing i wanted to point out is the obvious and eerie similarities between the divide between "femaleness" and "maleness", or "femininity" and "masculinity", and the described divide between the right and left hemispheres of the brain.

regardless of what is or isn't neuroscience truth, i think this at least suggests that there's some kind neurological basis for why we as humans continue to fall into these traps, and that it's a very easy trap to fall into. in a sense maybe if we take the time to understand this, we're kind of escaping some of the weaknesses of our biological programming and reprogramming ourselves.

in a sense, digital games seem to embody the kind of mechanical, virtual, fixed way that favors the left brain's point of view. but there's also something strangely...resistant about games. there's something fundamentally unknowable about them to us, and because of that we still kind of fear them. no matter how much we vie for mechanical perfection in the worlds we make, some bug in the system inevitably seems to push back at us and subvert our desire to beat it down and fashion it into our perfect utopian visions. this might be true in all art, but with games because there's still something so new and visceral, and upsetting about them to us.

there's this idea, a sort of trend in games spaces now of games approaching something "real" on the horizon - either in the strict material terms, as in being representational of real human environments in terms of look or feel. like in AAA games. or representing of something we understand as being part of the human experience, like in a direct personal, autobiographical videogame.

but this "reality" is really only an idea we have of reality, an idea that's created and maintained by our culture, an idea that's slowly slipping into the water and many people are frantically trying to grab onto the last still sinking bits of it to make any kind of sense of what's happening in the world.

in art, this is kind of goes with the divide between what we think of as modern and post-modern. or about high/low art.

it's in these dichotomies:

but digital art is completely changing the ways that art is made, completely exposing and making irrelevant existing models of thinking about and evaluating art in ways that could've only been in our wildest imagination in the past.

in visual art, now we have:

painting

vs. comic art, but also

digital art (this is from a hubble telescope photo). or god forbid

pixel shit

in music: symphonies or (more contemporarily)

the album as great cultural event vs.

digital mixtape/soundcloud/bandcamp or god forbid

chiptune or midi music

movies:

feature-length film vs.

digital short, or god forbid:

let's play

in the written word:

the grand, sweeping novel

vs. poem or short story, or god forbid:

IF/twine game, or even more god forbid:

fan fiction

and at all the end of all these different totem poles of expressive artistic worth we have videogames and their related offshoots scraping the bottom of the barrel. and so we can effectively understand their existence as novelties, or something cute, or machines that can be tweaked, or objects to be fetishized, but not anything more than that. we admire them for how completely and obediently machine-like they can be, and yet we laugh at their "videogamey" weirdness like it's a horrible, garish, weakness.

to go back to Erin's essay:

most great “female” minds have created effective pieces through working in relatively simple media, rather than attempting to control extraordinarily large projects with many variables.

the vast majority of female brilliance is lost...

femaleness... femininity... is lost.

we want to just arrogantly assume in the sphere of people who think and talk about art, that if a work is worth knowing, that if it's culturally significant that it will eventually in one way or another make itself known to us.

but what if that isn't true at all? what if something that could be a great, transformative work in one context disappears every week or every month, because its creators weren't in the right place in the right time, or no one around them cared or understood.

what about voices outside our own culture? what about great works not done in English, not done for western culture's needs and values? do we even think or care about them? do we even know they exist? do we have any conception of who they are outside a vague, racist, xenophobic conception we've formed of an other, or outside of a conception of existence that we have in our culture? how much of what they do will change the course of what we do? how much are we even allowing for that possibility?

let's just put this out there. making something uncommercial is not a weakness. not having or being able to have a flashy, clever hook is not a weakness. not having or being able to have a large promotional campaign that tries to establish why your thing is the greatest and most culturally significant new thing this month is not a weakness. not making or being able to make something with a large number of variables is not a weakness.

we want to say we're not being swayed by definitions, that we don't listen to the talk and that we're being open-minded and understanding. that we don't love to romanticize ideas of lazy, meaningless perfection at the expense of an other not so easily asserted, not so easily understood, not so easily accepted. that if something truly new and different came along we'd be able to greet it with open eyes and ears and we wouldn't send it away or become angry or laugh at it or try to destroy it or co-opt to it to use it to further our own ends.

but that's bullshit. because that's our culture. that's how we've been raised to view the world. but it's not just about us or the actions we take. unless we are aware of just how much exists outside our own sphere of self-interest, then we fall into the trap of the western, left-brained, "male", "masculine" way of thinking. and in turn, we will destroy ourselves.

there's this image from the freeware PC game Yume Nikki. you're a girl who goes to sleep in her empty apartment, only to wake up and walk through the door to find herself standing stand in a strange, uncertain purgatory-like space: a world through several different doors. the world seems to contain all sorts of arcane rules, and expand amorphously infinitely in all kinds of different directions. the further you go, the bigger the mystery seems to grow and the more questions you have. but these questions are never really answered. there is an ending, but the ending is not really the important part of this world.

i suppose this all comes back to that if we really want our answers of how to look at art, and games, and identity, and what to do with our lives we should be looking inward, and not be afraid to be scared, or disturbed, or disappointed, or disgusted - because we have a lot to learn about ourselves.

p.s. (i'll come back and source the images at some point soon).

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

an in-depth look at Doom Episode 1

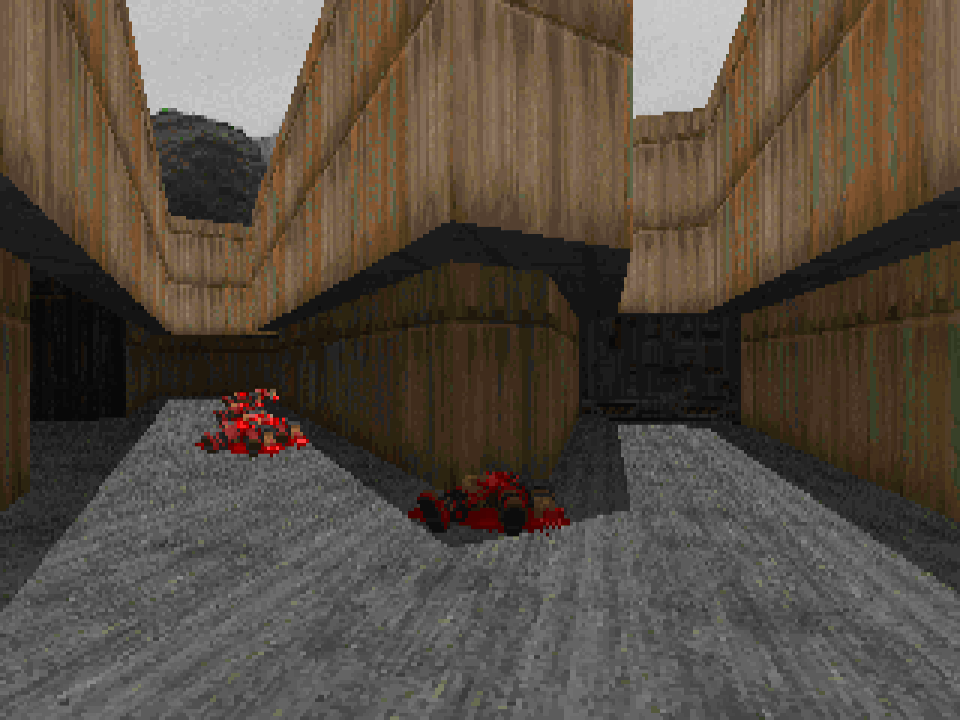

in the past week i did a few videos looking back at the design of "Knee Deep in the Dead", the original shareware episode of Doom for the game's 20th anniversary (coming up this December). part of my goal was to show why the game, and this episode in particular, has held a strong hold over so many people even 20 years later. i'm not sure whether i really succeeded or not since these videos are fairly off-the-cuff, but hopefully people will get something useful out of them. another part of my goal to show what makes Doom fundamentally different from the current FPS games it's supposed to have spawned. indeed - those games don't really seem have much of anything that comes close to resembling Doom as far as the design of the spaces or the direction of the experience goes. Doom still seems as completely foreign and of another world as it ever has, maybe even moreso.

one thing about the first episode that's clear from both playing back through it and from reading John Romero's design rules (mentioned in the video) beforehand: there's an insistence on a very abstract, but very specific set of rules tailored for the engine the game is made in. the spaces may feel "real" insofaras they are detailed, or their shapes or textures might resemble existing structures in our world - but there's nothing particularly functional about them as architecture outside of the context of the game. and yet you don't feel that at all, as the player. the world makes complete sense once you become acquainted to its language.

and that's what the first episode, in particular, does very well - bringing the player into the language of this very strange, very new kind of experience (when it came out in December 1993) while also providing a surprisingly coherent arc. yet it also subverts the rules it sets out to establish in many subtle but noticeable ways. no design idea is ever exactly repeated in the same way - there's always a new or different twist put on it to stay surprising. if the player starts out in an enclosed, safe area in one map, they'll start out in an open area with enemies in the next. ideas that might seem monotonous on paper come to life in the game because of all the little details and juxtapositions placed in front of you. no part of this episode ever feels like a tutorial or a trudge, because there's no need to tutorialize to get you up to the pace of the story or whatever in the first place. Doom is not trying to be anything other than it is, or tell you it's anything else than what it is. the story is the experience.

that's not to say this is the only valid way to approach to design. it's standard practice in the Doom community to talk shit about Tom Hall or Sandy Petersen's levels for not being as open or elegant or taking advantage of the engine's architecture so self-consciously. a lot of that is they just had less time to work on things, or were part of a compromised, half-realized vision. but that ignores the very strange and interesting ideas that lie in the other two main episodes, even if they don't have the benefit of coming together like in the first. not to mention that sometimes John Romero's maps feel almost silly for their level of interconnected-ness, like he was just trying to make singleplayer levels that doubled as multiplayer levels. but the continual return back to these specific pre-defined design rules create spaces that feel consistent to each other when they might not be otherwise, and i think is a big part of explaining why this first episode still contains the kind of allure it does.

all three videos are here for you to enjoy. look for more videos from me about Doom in the coming month or two, as well as an article about one of my favorite (if not my favorite) Doom mod that's coming soon. enjoy!

Friday, October 11, 2013

Fuck Festivals

fuck festivals.

i say this after having a wonderful time at IndieCade last week, and having just submitted my game Problem Attic to the IGF a few days ago.

the expectation placed on any so-called "indie game" to distinguish itself from the pack is much, much higher now. this might seem like a good thing, right? there are a lot more games now, so the stakes should be higher - and the games should be better, right? it, of course, depends on how you define "better". but this expectation has little to do with artistic or creative ambition and a lot to do with how professional-looking the game is. the end goal the forwarding of these games serves is to make "smaller games" become a new, viable, sustainable part of the games industry. everyone knows that Minecraft/Humble Bundle make tons of money, so a lot of people are pouring a lot of resources into getting in on that money.

this is a pretty violent shift from even five or six years ago, when a game like Passage was praised for being a unique achievement in game storytelling - where it was seen as a wildly left-field part of a new artistic vanguard. now it's becoming more apparent that a game like Passage was extremely lucky to benefit from there not being much else around to diminish it. now we can also see more clearly how conservative of the narrative of that game is in many ways - about a man and a woman and compromises they make, and how cliched the ideas behind it have become. now we can see how many games tried to be as artistically ambitious and less essentialist (i'm thinking of something like increpare's "Home") but never got nearly as much attention. now it would just look like a little experiment, one of many out there. it might get some coverage on a few indie gaming sites or get posted on freeindiegam.es and then that would be it. the conversation wouldn't sustain itself because there'd be something new to replace it in a week or less.

yes, it's easier to make a game than ever. the tools are much more accessible than they ever were before. and no, i'm not a person who believes that everyone making games (or art in general) is in any way bad at all. it's a wonderful thing, especially for the legions of the population who would otherwise be intimidated away from even attempting to try to make a game.

yet it's also hard to know in what spaces those games will be appropriately recognized and respected. things like the IGF and IndieCade might seem to be those spaces, but actually serve well those who have the ability to engage in a sustained PR to promote their games. this obviously benefits people with more resources and connections, who are almost universally not the type of people who would normally be scared away from making games. this is no secret. these festivals exist as a way to inject lifeblood into the games industry, or to legitimize games in the eyes of other industries like the film industry, not to subvert them.

festivals are supposed to be a bastion for new, ambitious developers to bring their game to a wider audience. but are festivals really developer friendly at all? for most developers, it's 95 dollars for the small hope that your game will reach a larger audience. except that it's more or less impossible for your game to be nominated unless you've waged an extended PR campaign for your game or are already a well-known developer. even for those who get in, they're expected to fly out to a conference and stay there (a flight which may or may not be paid for, other accommodations and food/drinks which almost certainly won't) and stand in front of a screen in a crowded expo floor for hours on end as people while people stumble their way through their game. this might be an acceptable sacrifice if there was just one festival - but there are many (the IGF being still the biggest) and there are a great number of games being exhibited at each of these festivals. each game is like a little tidbit, a little unit of ideas or concepts to be gorged on and eventually become absorbed into the industry. and so festival settings are fundamentally not served at all for slower or longer games - and particularly for text-based games. we don't value what these games may or may not have to offer. the nuances get glossed over because of the setting. we gorge on each one rapidly and leave. this is how we've been taught to treat videogames.

and personally, as someone who's designed a couple deliberately abstract games, there's nothing that sounds more like agony to me than being expected to explain and justify my game to any random person who walks by and plays it for five minutes. the Steam deal promised to developers nominated for last year's IGF was certainly a good thing, but that's only one festival of many - and a lot of the developers lucky enough to have the kind of PR clout to get in with the judges are also probably lucky enough to get on Steam without needing a nomination.

i admit it. some of these are my own realizations after designing a game (the aforementioned Problem Attic) that was in many ways unique and artistically ambitious, but i also recognized would not in any way be "festival-friendly". in itself, it might seem like a ridiculous idea that an artistically ambitious game wouldn't be "festival-friendly" - but in fact it makes perfect sense. festival jurors tend to self-consciously cherry-pick and reward the things with the most buzz. why? in order to make games more of a cultural event, for one - and to reward games which have managed to achieve some level of cultural penetration. there's also the practical matter of judges are going to naturally gravitate towards games or developers that they've already heard of, especially among the waves of games they haven't. and also to be what a good friend of mine calls a "photogenic indie" - something that's unique in maybe one or two ways but manages to overall have highly agreeable, unambiguous presentation. that's what people want to play, after all, right? they want the gloss, not the ugly, gross shit that shows its videogamey seams. that's what prominent members of the indie community or events like the IGF or IndieCade want to forward as examples of videogame expression.

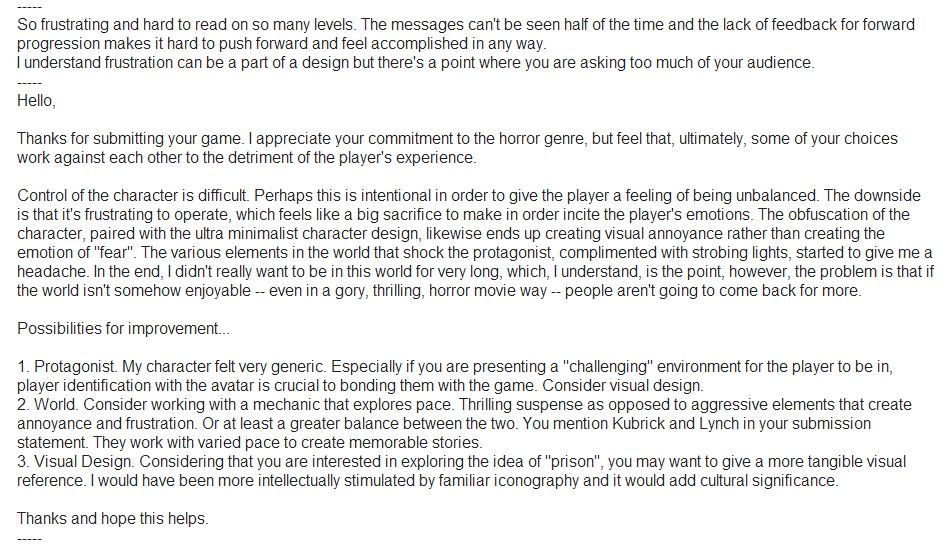

i will say that IndieCade was in several ways a lovely, forward-thinking event. it made an effort to have events like Night Games that the public could attend (though the lines were way too long for them), and also stayed lax about checking badges, allowing people to go to talks they might not be able to get into if they really wanted to. but as far as the festival goes, i've also received some of the most condescending feedback i've ever had. here are the two worst offenders (click to make it larger):

one judge says i'm "asking too much of my audience", the other seems to interpret my very intentional aesthetic choices as the fact that i must be clearly an inept and/or confused beginner (that i'm female likely plays into this), or else i clearly wouldn't have made a game like this.

i want to be clear that i don't want to make it out like i'm an exception, or that this is just about me. in many ways i'm maybe pretty lucky. i have enough friends to where if i kept waging a public PR campaign i might actually be able to get recognized in spite of how strange the things i make are, or how unpopular some of the sentiments i express in writing are. but that's not the point. the point is to aspire to have some kind of fair chance for people who can't, or won't engage in this. the point is to emphasize the people who are really, truly doing the most ambitious and crazy and unique things with videogames, and not the ones who are friends with the most judges, or who are making the most "photogenic" games. and i don't think it's possible for this to happen in any real way in the climate of these festivals.

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

re: fuck videogames

i did a talk somewhat based on (though heavily expanded) my original response to Darius Kazemi's Fuck Videogames at the No Show Conference in Boston. the text of the talk, which is also meant to stand alone as its own article is formatted here: http://www.ellaguro.com/refuckvideogames/

i'm also planning on making http://www.ellaguro.com my personal webpage when i get around to it, though i will probably still post articles on here for at least awhile.

i'm also planning on making http://www.ellaguro.com my personal webpage when i get around to it, though i will probably still post articles on here for at least awhile.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

The Talk of Magicians

today marks the 5th anniversary of the first release of Braid. i was going to write a eulogy of sorts, but it came at a bad time and i decided that Braid has already been picked apart so endlessly that i didn't feel a particular desire to contribute any more to it. then it occurred to me i already had an unpublished but article from early March of this year with some added edits i made today that delved into some of the issues i was planning on bringing up in the Braid post in a strange, roundabout way. it seemed oddly apt, and i don't quite know why this article never made it online anyway. so... without further ado, here you go:

(be warned, there are some spoilers for Corrypt!)

=====================================================

The Talk Of Magicians

"If Corrypt had more-polished graphics and sound, and were a bit longer, 100X-1000X as many people would play it...and it would make a good living for the developer" Braid developer Jon Blow tweeted. Other commercially-successful game devs followed suit: Hundreds developer Greg Wohlwend said in the same twitter conversation that he and Spelltower developer Zach Gage "agree(d) with jon" and that if Corrypt dev Michael Brough “worked on the visuals, the game would then be more accessible to outsiders". Blow, Wohlwend, and Gage then laid out advice for Brough on how to sell his game. Brough had for some reason set the original price on the app store at 1.00, which he changed to 2 dollars shortly after. "Part of it is building a name for yourself. these designs are good enough that you could build a base of people who would pay $10/$20 for whatever you do..." Blow said. Wohlwend agreed, and emphasized that by setting the price higher he'll "grow a following that will pay for (his) quality game design."

A few weeks prior, New Zealand-born, UK-based game developer Michael Brough posted on his blog re: his future prospects of full-time game development: "I expect to keep going for another year or two and then have to give up and get a real job". Indeed - according to his post, the only thing that brought Brough much money in 2012 was his game Vertex Despenser, which was a part of an Indie Royale Bundle that just happened to contain a pack of several titles from the commercially successful Serious Sam franchise in it. Still, 2012 was a productive year for Brough: he had four of his games in the app store: O, Glitch Tank, Zaga 33, and Corrypt. Shortly after making this post, his game Vesper.5 was nominated for a Nuovo award at this year's IGF. Brough's recent shout-outs for Corrypt from more high profile game devs like Blow, Canabalt creator Adam Atomic, and NYU Game Center director Frank Lantz (in an app store review) have also no doubt helped him get some more exposure since then. He even has been profiled recently in an issue of Wired.

But the value of this kind of social currency is becoming increasingly vague and hard to parse. A month after Brough's post, UK game developer Sophie Houlden, in a post reviewing her past few years as a full-time indie, wrote "I have enough money left to eat for a month, maybe two". Her situation is not particularly unique among indies. Brough's lack of app store success shows how difficult it can be to make any degree of living off selling one's games on distribution services. And Steam Greenlight, a supposed help for users to vote for lesser-known developers to get sold on the popular digital distribution service Steam, is not exactly what one might call a friendly venue for slightly offbeat developers like Brough or Houlden either. Putting aside the controversy surrounding the 100 dollar entry fee, one look at the list of Greenlit games and you'll see a very conservative cross-section of the "indie" community. Many even appear to be unfinished (On Greenlight, Houlden tweeted: "Greenlight is great, how else would unfinished games get a steam deal instead of hundreds of finished games!"). If it's much of a surprise to anyone that these are the games the Steam community would choose to put on the distribution service, they haven't been paying very much attention. But it does certainly dispel the oft-repeated cliche that the best or most interesting ideas eventually rise to the top.

==========================================

Walking into the world of a Michael Brough game feels like stepping inside of a machine that has existed for a very long time before you ever entered into it. His obsession with hyper-intricate backgrounds with interlocking networks of symbols, like these circuit board-style designs for his game Helix feel like occupying the nervous system of a living being - which makes no concessions to you, nor does it make any effort to translate its logic into human language. There's a constant tension between this alienness and your in-game character, of just being in the environment and then having to manipulate it to serve your own ends and progress in the game.

Brough's games are also particularly notable in the way they have no seeming desire to make concessions to players while still being somewhat approachable and "game-like" in terms of mechanics. He does all the visuals and sound in his games - and largely because of this consistency, across genres and styles they all feel like self-contained worlds. These worlds can be cryptic and unfriendly, often hostile to many players. The Wired article (somewhat bafflingly) describes them in its title as "ugly".

This "ugliness" is actually a highly-refined, organic style of Brough's that somehow manages to feel both coarse and delicate. Brough has been using this style across a majority of his games, but Corrypt addresses the possible intent behind the aesthetics by encoding strong environmental overtones into it. In Corrypt, your character awkwardly shuffles through and pushes a series of boxes and manipulates the environment to complete side quests and collect mushrooms and gems and keys. After your character pushes enough boxes to collect enough items, he has the power to spend them as currency to buy magic from a magician (which other NPCs in the game warn him to stay away from). Buying magic allows the player to completely alter the fabric of the environment, permanently destroying and warping it in all kinds of maddeningly unpredictable ways, in order to gain every last gem. This process enacts a lot of fear and anxiety in the player, especially as he or she moves further along, from seeing what her or his actions have wrought.

It's hard not to see the magic in the game as some sort of allegory on human beings' never-ending thirst for more resources, and the irreparable damage it enacts on the environment. It suggests, especially taken with his other works like Vesper.5, that environments are delicate spaces that need to be accepted on their own terms in order to really be understood at a deeper level.

These greater themes seem to be absent in the little critical writing that does exist about his games - they're not mentioned anywhere in the Wired article, nor in this detailed critical reading, which focuses solely on the mechanical aspects of his games. The strangeness and beauty of the environments become a marginalized backdrop to a game seen as only remarkable from a design perspective - something the game even seems to mock with its flat looking aesthetics and its big, square block pushing and its few mock-JRPG miniquests in the beginning.

Not only have Blow and other well-known devs failed to understand that these subtle aesthetic choices are actually an integral part of the experience of playing Corrypt - they've actually completely missed what the game is trying to communicate in the first place. The more I think about it, the more the gap in perspective and intentions between designers of "polished games" like Blow and more self-expressive, experimental types Brough seems to widen. Maybe this also explains Brough's seeming indifference about how he priced Corrypt in the app store.

Many commercially-focused indie devs might like to say that they intend to use their games to create a deep, thoughtful space through the design. But it's hard to skirt the reality that those devs are often just aiming to create smaller-scale, slightly off-beat versions of already commercially successful formulas. And when they aren't, the focus on polish and polish and on this somewhat impossible goal of reaching a mass audience - in a way that becomes oddly prescriptive and cynical and self-limiting about content, and erasing of the circumstances of those like Brough who maybe don't have the time or money or interest to endlessly "polish" one game. Like Blow et al aren't aware that making something which might not be accessible, or at least their conception of accessible, to a large audience could be anything but a lazy and self-defeating artistic choice in the end. Like they're almost offended that Brough refuses being their protege or following the same career path as them. The message to Brough in Blow's and others' tweets seems clear: either play by the rules or don't expect to make any sort of living off what you're doing.

====================================

Still, Brough is lucky. His struggles reaching a wider audience were just recently profiled in more detail in the previously mentioned Wired article. It remains to be seen whether this exposure will let him keep making games full-time - but in private conversation, he told me "I want to be clear... I don't want to be using the image of poverty to get attention" and that him and his wife are comfortable for now. He also acknowledges his privilege in a recent blog post: "If I'm any good at what I'm doing now, it's only through having had the chance to devote an incredible amount of time to it. I'm fortunate. Being able to put years of unpaid full-time work into something before seeing anything back from it is an incredible privilege."

If we know anything about games, we know that the people who make and sell games will need to find ways to make their games resonate with larger audiences outside of "gamers" if they want a higher degree of cultural penetration. What this might mean, though, no one can really say. Successful indies are, after all, a privileged minority. I strongly suspect that a small percentage of games in the App Store (things like Spelltower, Hundreds, or Canabalt by previously-mentioned devs) make a vast majority of the money, but without anything concrete to prove it, it's still not a particularly rewarding path for most developers to take (to put it lightly). "Indie games" as we know them are barely now five years old, but the idea of a freak, Canabalt-type success now seems all but impossible now, let alone a Minecraft-level one. But the narrative that gets endlessly picked apart and reiterated and grossly fetishized by the press and by vulture-like indie devs is the one of the commercial success stories like Minecraft or Braid or Super Meat Boy - even though Sophie Houlden's (or thousands of less well-known developers') experiences are much more typical.

To Blow or Wohlwend, a talented designer accepting that his or her artistic choices aren't going to make she or he a lot of money might sound like bad a move. But then, the idea that any self-identifying artist finds this to be a not sane or valid perspective to have about his or her art just shows how insane and money-fueled the current climate of videogames, indie or not, is.

It shouldn't be so revolutionary to suggest that the world of a Michael Brough game might be giving players something meaningful - not just mechanically, but aesthetically, that commercially-focused devs like Blow or Wohlwend's games are not. In a world where a majority of indie games aren't known at all outside a relatively small group of insiders, his search for depth, both mechanical and aesthetic, certainly shows a much greater respect towards the works of very un-techie factions of the visual art and music world than his aesthetic's detractors' do.

The excitement that veils something much more sinister - the odd obsession with an unobtainable systemic perfection, often fueled by unrelated emotional pain or longing fostered by society - the thirst for money masked in frenzied experiments to remodel human behavior - an utter cluelessness and indifference to different modes of values or anything and anyone not in the room. This is the language of tech culture of the early 21st century, and the language implicitly embraced by Braid (even if it tries and fails to be critical of this from within). It's a language that just serves as another sad mirror, another small subset of what we are enacting on the earth and all the pain it causes - social, spiritual, environmental. It's a language that Corrypt, in all its seemingly insubstantial, clunky, box-pushing glory, is acutely aware of. It's a language that Corrypt is very critical of in both its aesthetics and design, in a way that Braid misses the boat on.

Conventional wisdom says that in the current market for indie/mobile/social games, players will eventually reach a point when they become so turned off by the absolute oversaturation of disposable mass-market dross flooding distribution services. Talk is cheap, and talk, in the end, usually fails to account for people's changing needs and values. Then, we can hope, they'll start to actively seek out things which are more mechanically and aesthetically rich. But this could also be false optimism. Maybe the culture of games is so deeply channeled towards the most surface, dumbed-down communication in that the only hope for the future is the freaks coming in from the outside and trying create an entirely new model. Thankfully, Michael Brough is happy to oblige.

Whatever happens, let's pray to God the shovelware market suffocates itself sooner than later - because right now, Brough's games are some the few that offer any sort of real, untainted route out of the unending waves of shallow, manipulative entertainment. Maybe we'll even reach a point in the future where all the highly calculated programmers and businessmen with seemingly unending confidence and resources who make games - or, as Corrypt would call them: magicians, come face to face with a reality they can't undo anymore.

(be warned, there are some spoilers for Corrypt!)

=====================================================

The Talk Of Magicians

"If Corrypt had more-polished graphics and sound, and were a bit longer, 100X-1000X as many people would play it...and it would make a good living for the developer" Braid developer Jon Blow tweeted. Other commercially-successful game devs followed suit: Hundreds developer Greg Wohlwend said in the same twitter conversation that he and Spelltower developer Zach Gage "agree(d) with jon" and that if Corrypt dev Michael Brough “worked on the visuals, the game would then be more accessible to outsiders". Blow, Wohlwend, and Gage then laid out advice for Brough on how to sell his game. Brough had for some reason set the original price on the app store at 1.00, which he changed to 2 dollars shortly after. "Part of it is building a name for yourself. these designs are good enough that you could build a base of people who would pay $10/$20 for whatever you do..." Blow said. Wohlwend agreed, and emphasized that by setting the price higher he'll "grow a following that will pay for (his) quality game design."

A few weeks prior, New Zealand-born, UK-based game developer Michael Brough posted on his blog re: his future prospects of full-time game development: "I expect to keep going for another year or two and then have to give up and get a real job". Indeed - according to his post, the only thing that brought Brough much money in 2012 was his game Vertex Despenser, which was a part of an Indie Royale Bundle that just happened to contain a pack of several titles from the commercially successful Serious Sam franchise in it. Still, 2012 was a productive year for Brough: he had four of his games in the app store: O, Glitch Tank, Zaga 33, and Corrypt. Shortly after making this post, his game Vesper.5 was nominated for a Nuovo award at this year's IGF. Brough's recent shout-outs for Corrypt from more high profile game devs like Blow, Canabalt creator Adam Atomic, and NYU Game Center director Frank Lantz (in an app store review) have also no doubt helped him get some more exposure since then. He even has been profiled recently in an issue of Wired.

But the value of this kind of social currency is becoming increasingly vague and hard to parse. A month after Brough's post, UK game developer Sophie Houlden, in a post reviewing her past few years as a full-time indie, wrote "I have enough money left to eat for a month, maybe two". Her situation is not particularly unique among indies. Brough's lack of app store success shows how difficult it can be to make any degree of living off selling one's games on distribution services. And Steam Greenlight, a supposed help for users to vote for lesser-known developers to get sold on the popular digital distribution service Steam, is not exactly what one might call a friendly venue for slightly offbeat developers like Brough or Houlden either. Putting aside the controversy surrounding the 100 dollar entry fee, one look at the list of Greenlit games and you'll see a very conservative cross-section of the "indie" community. Many even appear to be unfinished (On Greenlight, Houlden tweeted: "Greenlight is great, how else would unfinished games get a steam deal instead of hundreds of finished games!"). If it's much of a surprise to anyone that these are the games the Steam community would choose to put on the distribution service, they haven't been paying very much attention. But it does certainly dispel the oft-repeated cliche that the best or most interesting ideas eventually rise to the top.

==========================================

Walking into the world of a Michael Brough game feels like stepping inside of a machine that has existed for a very long time before you ever entered into it. His obsession with hyper-intricate backgrounds with interlocking networks of symbols, like these circuit board-style designs for his game Helix feel like occupying the nervous system of a living being - which makes no concessions to you, nor does it make any effort to translate its logic into human language. There's a constant tension between this alienness and your in-game character, of just being in the environment and then having to manipulate it to serve your own ends and progress in the game.

Brough's games are also particularly notable in the way they have no seeming desire to make concessions to players while still being somewhat approachable and "game-like" in terms of mechanics. He does all the visuals and sound in his games - and largely because of this consistency, across genres and styles they all feel like self-contained worlds. These worlds can be cryptic and unfriendly, often hostile to many players. The Wired article (somewhat bafflingly) describes them in its title as "ugly".

This "ugliness" is actually a highly-refined, organic style of Brough's that somehow manages to feel both coarse and delicate. Brough has been using this style across a majority of his games, but Corrypt addresses the possible intent behind the aesthetics by encoding strong environmental overtones into it. In Corrypt, your character awkwardly shuffles through and pushes a series of boxes and manipulates the environment to complete side quests and collect mushrooms and gems and keys. After your character pushes enough boxes to collect enough items, he has the power to spend them as currency to buy magic from a magician (which other NPCs in the game warn him to stay away from). Buying magic allows the player to completely alter the fabric of the environment, permanently destroying and warping it in all kinds of maddeningly unpredictable ways, in order to gain every last gem. This process enacts a lot of fear and anxiety in the player, especially as he or she moves further along, from seeing what her or his actions have wrought.

It's hard not to see the magic in the game as some sort of allegory on human beings' never-ending thirst for more resources, and the irreparable damage it enacts on the environment. It suggests, especially taken with his other works like Vesper.5, that environments are delicate spaces that need to be accepted on their own terms in order to really be understood at a deeper level.

These greater themes seem to be absent in the little critical writing that does exist about his games - they're not mentioned anywhere in the Wired article, nor in this detailed critical reading, which focuses solely on the mechanical aspects of his games. The strangeness and beauty of the environments become a marginalized backdrop to a game seen as only remarkable from a design perspective - something the game even seems to mock with its flat looking aesthetics and its big, square block pushing and its few mock-JRPG miniquests in the beginning.

Not only have Blow and other well-known devs failed to understand that these subtle aesthetic choices are actually an integral part of the experience of playing Corrypt - they've actually completely missed what the game is trying to communicate in the first place. The more I think about it, the more the gap in perspective and intentions between designers of "polished games" like Blow and more self-expressive, experimental types Brough seems to widen. Maybe this also explains Brough's seeming indifference about how he priced Corrypt in the app store.

Many commercially-focused indie devs might like to say that they intend to use their games to create a deep, thoughtful space through the design. But it's hard to skirt the reality that those devs are often just aiming to create smaller-scale, slightly off-beat versions of already commercially successful formulas. And when they aren't, the focus on polish and polish and on this somewhat impossible goal of reaching a mass audience - in a way that becomes oddly prescriptive and cynical and self-limiting about content, and erasing of the circumstances of those like Brough who maybe don't have the time or money or interest to endlessly "polish" one game. Like Blow et al aren't aware that making something which might not be accessible, or at least their conception of accessible, to a large audience could be anything but a lazy and self-defeating artistic choice in the end. Like they're almost offended that Brough refuses being their protege or following the same career path as them. The message to Brough in Blow's and others' tweets seems clear: either play by the rules or don't expect to make any sort of living off what you're doing.

====================================

Still, Brough is lucky. His struggles reaching a wider audience were just recently profiled in more detail in the previously mentioned Wired article. It remains to be seen whether this exposure will let him keep making games full-time - but in private conversation, he told me "I want to be clear... I don't want to be using the image of poverty to get attention" and that him and his wife are comfortable for now. He also acknowledges his privilege in a recent blog post: "If I'm any good at what I'm doing now, it's only through having had the chance to devote an incredible amount of time to it. I'm fortunate. Being able to put years of unpaid full-time work into something before seeing anything back from it is an incredible privilege."

If we know anything about games, we know that the people who make and sell games will need to find ways to make their games resonate with larger audiences outside of "gamers" if they want a higher degree of cultural penetration. What this might mean, though, no one can really say. Successful indies are, after all, a privileged minority. I strongly suspect that a small percentage of games in the App Store (things like Spelltower, Hundreds, or Canabalt by previously-mentioned devs) make a vast majority of the money, but without anything concrete to prove it, it's still not a particularly rewarding path for most developers to take (to put it lightly). "Indie games" as we know them are barely now five years old, but the idea of a freak, Canabalt-type success now seems all but impossible now, let alone a Minecraft-level one. But the narrative that gets endlessly picked apart and reiterated and grossly fetishized by the press and by vulture-like indie devs is the one of the commercial success stories like Minecraft or Braid or Super Meat Boy - even though Sophie Houlden's (or thousands of less well-known developers') experiences are much more typical.

To Blow or Wohlwend, a talented designer accepting that his or her artistic choices aren't going to make she or he a lot of money might sound like bad a move. But then, the idea that any self-identifying artist finds this to be a not sane or valid perspective to have about his or her art just shows how insane and money-fueled the current climate of videogames, indie or not, is.

It shouldn't be so revolutionary to suggest that the world of a Michael Brough game might be giving players something meaningful - not just mechanically, but aesthetically, that commercially-focused devs like Blow or Wohlwend's games are not. In a world where a majority of indie games aren't known at all outside a relatively small group of insiders, his search for depth, both mechanical and aesthetic, certainly shows a much greater respect towards the works of very un-techie factions of the visual art and music world than his aesthetic's detractors' do.

The excitement that veils something much more sinister - the odd obsession with an unobtainable systemic perfection, often fueled by unrelated emotional pain or longing fostered by society - the thirst for money masked in frenzied experiments to remodel human behavior - an utter cluelessness and indifference to different modes of values or anything and anyone not in the room. This is the language of tech culture of the early 21st century, and the language implicitly embraced by Braid (even if it tries and fails to be critical of this from within). It's a language that just serves as another sad mirror, another small subset of what we are enacting on the earth and all the pain it causes - social, spiritual, environmental. It's a language that Corrypt, in all its seemingly insubstantial, clunky, box-pushing glory, is acutely aware of. It's a language that Corrypt is very critical of in both its aesthetics and design, in a way that Braid misses the boat on.

Conventional wisdom says that in the current market for indie/mobile/social games, players will eventually reach a point when they become so turned off by the absolute oversaturation of disposable mass-market dross flooding distribution services. Talk is cheap, and talk, in the end, usually fails to account for people's changing needs and values. Then, we can hope, they'll start to actively seek out things which are more mechanically and aesthetically rich. But this could also be false optimism. Maybe the culture of games is so deeply channeled towards the most surface, dumbed-down communication in that the only hope for the future is the freaks coming in from the outside and trying create an entirely new model. Thankfully, Michael Brough is happy to oblige.

Whatever happens, let's pray to God the shovelware market suffocates itself sooner than later - because right now, Brough's games are some the few that offer any sort of real, untainted route out of the unending waves of shallow, manipulative entertainment. Maybe we'll even reach a point in the future where all the highly calculated programmers and businessmen with seemingly unending confidence and resources who make games - or, as Corrypt would call them: magicians, come face to face with a reality they can't undo anymore.

Thursday, July 18, 2013

articles on Problem Attic

just wanted to give a shout out to the lovely people who have taken it upon themselves to write about Problem Attic. here's a list of several i've found:

- I played: Problem Attic by Joe Wreschnig

a short article with some great observations about the overall feel and intent of the game

- Problem Attic Thoughts by Kim D

some thoughts on how the game is played, and on the music and visuals

- The Creative Veil by Eli Brody

cool article not specifically about Problem Attic that talks about art that creates a sort of veil which hides the underlying process of how it was actually constructed.

- Absurdism in Games by Solon Scott

interpretation of Problem Attic as an "absurdist game", along with a couple other indie games.

- Glitch This: Problem Attic by Chris Priestman

article on indiestatik that went up the day i released the first version. i wish the author would've waited to reach the latter chunk of the game when things change up, but i appreciate the article nonetheless.

knowing that some people have had an intense enough reaction to be compelled to write about the game makes me feel very good. thanks again to everyone for sharing their thoughts!

- I played: Problem Attic by Joe Wreschnig

a short article with some great observations about the overall feel and intent of the game

- Problem Attic Thoughts by Kim D

some thoughts on how the game is played, and on the music and visuals

- The Creative Veil by Eli Brody

cool article not specifically about Problem Attic that talks about art that creates a sort of veil which hides the underlying process of how it was actually constructed.

- Absurdism in Games by Solon Scott

interpretation of Problem Attic as an "absurdist game", along with a couple other indie games.

- Glitch This: Problem Attic by Chris Priestman

article on indiestatik that went up the day i released the first version. i wish the author would've waited to reach the latter chunk of the game when things change up, but i appreciate the article nonetheless.

knowing that some people have had an intense enough reaction to be compelled to write about the game makes me feel very good. thanks again to everyone for sharing their thoughts!

Tuesday, June 25, 2013

Problem Attic news

first of all, the game's soundtrack is available here:

it contains 15 tracks (5 hidden to avoid spoilers) and several extras. it's 3 dollars or more.

second, the final, definitive version of the game is available here:

http://ellaguro.com/gams/problematticfinal.swf

6/30 UPDATE: the jump key in the above version is now the up arrow key, at the suggestion of a few people. let me know if that's easier.

6/30 UPDATE: the jump key in the above version is now the up arrow key, at the suggestion of a few people. let me know if that's easier.

right click and "save target as" if you don't want to play it in your browser. the mirror is updated, and it's here:

http://touch.gg/_stuff/problem-attic/

i also put the game up on gamejolt for the hell of it

http://gamejolt.com/games/platformer/problem-attic/15532/

http://touch.gg/_stuff/problem-attic/

i also put the game up on gamejolt for the hell of it

http://gamejolt.com/games/platformer/problem-attic/15532/

=========================================

what's changed? well, i decided to add another section to the game, which requires the player to go through some previously optional story elements. i felt it was too important for the understanding the overall experience not to have them in the game. the ending is also different - the sequences are more or less the same, but there's different music and the mood is different. it's a little bit more emotionally resonant and less cryptic for me.

save game transferring from a previous version is difficult. if you downloaded it over top of the previous file, then it should save your game. if you play from the mirror it also might save your game. otherwise, it won't. that's unfortunately how it works, and i can't really do anything to change it. i'm sorry there isn't a better option.

i felt like i wanted people to see those things in order to beat the game, though i understand it may be too late for people to want to play it through again anyway. at the very least, i have it updated in time to be judged for indiecade in the form i'm most happy with.

i'm officially closing the book on this game. i hope you've enjoyed it.

Friday, May 31, 2013

thoughts on Problem Attic

note: this post is spoiler-free. if you're looking for the download link/instructions, they're here.

2d mechanics-based platforming games are a punchline now. they're the cliche of indie games, best demonstrated by each of the three games covered in Indie Game: The Movie, which all fit very snugly into the category of what my friend Anna (Anthropy) calls "white dudes trying to remake Mario". i love Mario but am personally tired of all Nintendo did to establish games as consumer products marketed at kids and then the subsequent stranglehold Nintendo holds over any and all gamer "nostalgia". it strikes me as a disrespectful, abusive, parasitic relationship to have with the loyal fans of your (often really neat, admittedly) games.

i still felt like there was some interesting territory to explore with a 2d platformer, but it's been mined so heavily by so many games that i felt like other avenues needed to be explored so much more and i didn't want to touch it any time soon. honestly, it just felt a little boring and pedestrian of a way to present a game. i feel like the short era of the dominant indie puzzle platformer is, if not dead, at least on life support - and i am fine with that, honestly.

i would like to say i had some divine change of heart that led me to working on a 2d platformer, but that's not true at all. i've been trying to phase out of indie game stuff and into some sort of music career because i'm finding the environment of indie games as one that has many serious holes in terms social or artistic or human enrichment for me. and i say that having met a wonderful support network through people involved in games, and having met several wonderful, talented people who are taking things in the right direction. but i'm tired of seeing of people go apeshit about the supposed deep meaning in things like Bioshock Infinite, or even supposed socially progressive crap like A Closed World. i understand that making a socially aware game is at least one step in the right direction in a culture that's so hostile to it, but i think we could do so much better. and that's what motivates me to keep trying.

making anything vaguely larger-scale was not something i had any plans of doing. i made a game with my friend Andi McClure for last ludum dare called Responsibilities that i liked, but it never went anywhere after that weekend. i have so many friends who make games, and i knew i had interesting ideas and could do it, i was just anxious about learning the tools. it felt kind of insurmountable. and i've made levels and stupid little small games, so i'm not inexperienced. i wanted to prove to myself that i could make a game all by myself for ludum dare, and that was really it. i started to learn stencyl and quickly discovered the thing i could do the most effectively was a platformer, so i went with that - and it ended up fitting in well with the idea i had for an art style from some random ms paint sketches i'd made.