| greetings! this is a very long post about video games and capitalism. feel free to take breaks if you need them. make sure to stick around till the end, if you can. plz enjoy. and support me on patreon if you like (and read this post on patreon here for free if you don't like orange). i have a new indie music-related podcast, by the way, in case you're interested in checking it out. anyway...... - liz |

"If silicon is prone to make your dreams come true

You could probably say the same thing about nightmares too"

- from 'The Future of History' by Tropical Fuck Storm

|

| the 0th Indie Game Jam |

almost exactly 10 years ago, i made an account on Twitter to promote a fake game called "Gloomp!"

whenever any space experiences a new wave of financial success and public scrutiny

unlike anything else that came before it, it leads to a lot of industry hype and speculation. the shift from 2D to 3D development as the norm in the mid-90's was a massive sea change that transformed the video game industry in profound ways. the onset of the internet and its increasingly large role in society and culture of the last thirty years is one of the most consequential events to happen in the past century. drastic shifts in technology that alter modes of being are not new. the endless supply of new products that dramatically change how we construct ourselves around them is one of the primary features of capitalism.

all of this is to say, i wasn't particularly sold on this new wave of excitement towards mobile and casual games at the time. to me what felt particularly strange was the intensity of the rhetoric around a certain subset of games, especially when placed in tandem with how tiny and narrowly focused the insights it felt like you could glean from each of these things as experiences was. mobile games like Canabalt were fun byte-sized little action stories that brought back some of the artistry of vintage coin-op arcade games.

social games that involved more human interaction like JS Joust could

get crowds of people interacting with each other in ways often lacking in a space that mostly involves being sedentary for long periods of time (though the critique re: JS Joust was often that you could

easily win if you were bigger/had longer arms). there are events focused on physical play like Come Out And Play that still attract a lot of attention and i can imagine will continue to do so as more people lack real-life communal spaces to gather together in. though the kinds of games they feature have never escaped being performed in very specific events and settings. some of which, like in school gym class or mandated corporate team-building exercises, feel pretty far from some of the grandiose theorizing about transforming society through play.

the main point was that these weren't new things at all. they were heavily informed by a fascination with the often underappreciated artistry of mechanically simple 80's video games and the hippie-infused New Games movement of the 70's. twenty- and thirty-year nostalgia cycles dominate so much cultural movement and are not a new phenomenon, of course. but this movement was deeply infused with an increasingly powerful streak of hyper-individualism pushed by the tech industry, which gave all of the rhetoric a special intensity. ever since the 90's, an increasing amount of power and money was being offloaded from other parts of society and onto tech industry entrepreneurs drowning in piles of cash. this only became more prevalent in wake of the Great Recession, which the tech industry seemed almost unscathed by. if you were in any space even vaguely tangential to technology at the time (which game development certainly was), it was completely impossible to escape the overwhelming predominance and full-throated embrace of this rhetoric. the tech industry had been fully empowered by the world to enact its beliefs on a massive scale.

allow me here to quote at length from a very influential (and prescient) critical piece about the tech industry by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron from 1995 called "The Californian Ideology" (emphasis in bold is mine):

"the Californian ideology has emerged from this unexpected collision of right-wing neo-liberalism, counter- culture radicalism and technological determinism - a hybrid ideology with all its ambiguities and contradictions intact. These contradictions are most pronounced in the opposing visions of the future which it holds simultaneously.

On the one side, the anti-corporate purity of the New Left has been preserved by the advocates of the 'virtual community'... Community activists will increasingly use hypermedia to replace corporate capitalism and big government with a hi-tech 'gift economy' in which information is freely exchanged between participants.... Despite the frenzied commercial and political involvement in building the 'information superhighway', direct democracy within the electronic agora will inevitably triumph over its corporate and bureaucratic enemies.

On the other hand, other West Coast ideologues have embraced the laissez faire ideology of their erstwhile conservative enemy...

In this version of the Californian Ideology, each member of the 'virtual class' is promised the opportunity to become a successful hi-tech entrepreneur. Information technologies, so the argument goes, empower the individual, enhance personal freedom, and radically reduce the power of the nation-state. Existing social, political and legal power structures will wither away to be replaced by unfettered interactions between autonomous individuals and their software.... The free market is the sole mechanism capable of building the future and ensuring a full flowering of individual liberty within the electronic circuits of Jeffersonian cyberspace."

the piece then goes on to talk about how much Californian ideology came out of a massive amount of public money and government influence spent towards developing the internet. these tools were, of course, greatly dependent on labor exploitation and the suffering of others to build and maintain the technology necessary for this. but it set the stage for the all-encompassing fantasy of a new virtual frontier; a frontier that goes back to the original American founding myth of the frontier settlers of the west.

and that rhetoric of "the new frontier" and "the wild west" was inescapable at the time in the indie game development sphere. these were not the type of people who were particularly happy or even very conscious of being implicated in critiques of Californian Ideology. in a podcast episode i did in 2021 about this period of time in the space with games researcher (and friend) Alex Ross, he mentioned the influence of famous counter-culture huckster Stewart Brand, his Whole Earth Catalog, and the idea of the "cowboy nomad" on thoughts expressed by prominent indie game figures like Jason Rohrer or Jenova Chen at the time. they often spoke in romantic ways which conflated the idea of personal success with larger social success. these were developers envisioning themselves as wandering empowered tool-users, or anarchist squatters roaming the countryside and creating a space for everyone around to inhabit through their own personal achievement and self-belief. they were, to be fair, by far not the only people in the game industry who bought into these sorts of notions. this tweet from last year by game industry legend John Carmack is a perfect embodiment of this way of thinking for me:

so anyway, if you played Braid for the first time in 2009 thanks to a friend's recommendation and your interest was piqued by its novel use of time-manipulation, you might start looking for conference talks on game design to follow during this time period. and you might quickly notice that there was a lot of talk on short experimental games like Rod Humble's The Marriage or Jason Rohrer's Passage at the time. the dominant discourse around these works often revolved around their ability to demonstrate how you, as a designer, can Do Things With Video Games. their key insights were how they stripped games to their bare essential dynamics and expressed something deeper underneath.

both of the above games

were often tearfully

presented by other developers at conferences as making meaningful and profound

statements that changed the way they thought about video games at a fundamental level. they appeared like lightning rods for many game industry people that sent them into a tizzy about how they constructed their larger life and work. these games signaled that video games had arrived, that they mattered now, and that they were shedding themselves of their sordid past as violent shooter games and mere objects of "fun".

longtime game designer and Game Developers Conference founder Chris Crawford, while talking to Rohrer for the documentary Us and the Game Industry (which my aforementioned game researcher friend Alex Ross likened to "a Scientology recruitment video for the indie games industry" and you can currently watch for free on Roku afaik), said something related to this that i think about a lot:

i can only imagine this desire to escape the sordid reputation of games fed the aura of excitement that hovered around influential industry people so visibly buzzing about an extremely spare prototype involving growing and shrinking squares, or a tiny 8-bit walking simulator. i can't imagine this happening at any other point in the short history of video games. the mainstream industry was awash in the time with gritty military-themed first person shooters and bloated open-world games. development cycles of AAA games had become increasingly more expensive, high stakes, and stifling of innovation.

the late 00's was also when i checked out of video games in

general as a casual consumer, because it just felt to me like so many games were becoming more samey and bland in their design and going in the wrong direction. unbeknownst to me at the time, a growing crowd of influential people in the video game industry were vocally advocating for new forms of innovation to break the industry out of its stupor of derivativity. and parallel to that, the idea of the self-styled entrepreneur was growing in power in larger culture. so the tech industry was increasingly in an excellent place to help empower some new individuals to "disrupt" the space with innovation.

in general, in broader culture it felt like games wanted more and more to be taken seriously as consequential art, but also didn't want to have the same scrutiny level applied to them as other art.

all of this applied even more to the indie space, which was growing in prominence and influence thanks to the breakout success of games like Braid and the sudden monumental juggernaut of Minecraft. to anyone who gleefully espoused the value of some formative indie works, you likely never were allowed to stop for very long to interrogate what questions the themes of games like Passage or The Marriage presented, and what they may say about troubling dynamics in gendered relationships. they were more just signifiers that represented that the possibility of deeper expression was there, and should be taken seriously and given more scrutiny. but the moment you applied more scrutiny and started to ask questions about the themes in the work, that was often handwoven off as irrelevant to the point at hand (which was, again, that Videogames Have Arrived).

this always begged the question for me (a question which remains unanswered): why is the vessel for this new wave of serious important experimental art games that are poised to transform the industry seemingly all about failing or dysfunctional marriages? the unintentionally funny jankfest

Façade from around the same period, co-authored by future military contractor Andrew Stern, was another notable example. and what's the deal with the oddly large number of games featuring dead wives, for that matter?

basically - even if you were willing to ignore how much this space was soaked thru with romanticized hyper-libertarian beliefs about cowboy nomads empowered by the tech industry, it was hard to ignore the implications of the themes that kept popping up within a lot of creative works. Rohrer's game The Castle Doctrine (based of a famous right-wing ideology about 'standing your ground'/property defense) was a particularly notorious example that Rohrer doubled down on in a bizarre post about self-defense and that defense was backed up by many in the space - which felt especially egregious coming in the wake of public outcry around the Trayvon Martin murder. and, much less egregiously, other notable indie games like Dear Esther, embodied the dead wife/death of marriage trope so common to art games at that point in a commercially-facing, mainstream accessible way. my favorite response to this whole odd phenomenon is the satirical game "The Virtual Museum of Dead-Wifery" by Lilith and Zoë Sparks, by the way.

but, for me, this underlined the point that these games perhaps weren't, in a sense, actually about what they were about. they were containers signifying the capability of larger meaning that could theoretically exist. they were meaning machines capable of eliciting empathy (a rhetoric that got even more intense later on in the 2010's around VR), but exactly how that empathy manifested itself was a placeholder. if games were to have a greater purpose in society, they simply must be able to do this. that capability of evoking empathy and containing larger meaning mattered far more than what specifically was being expressed.

so in that case, even though i don't think most people either got the joke or thought it was as funny as me (shout-out to Kepa from Rocketcat Games for getting on the train though), my fake game Gloomp! was a stand-in, for me, which represented the ideal form of art within the commercial indie game space of the time: an entity that is both transformative but also empty, without any particular meaning assigned to it. a squishy container for the over-romanticized ideal of transformative or meaningful 'play' that was poised to take over the space around it, but didn't correspond to anything in particular or make a statement about anything in particular. an object that signified importance in some kind of vague, market-friendly way, by virtue of simply being in the space at that particular time and place. a response to games like flOw that were so focused on the act of expression without having much of any interest in what, exactly, was being expressed. a perfect commodity, basically.

like most things, "Gloomp!" was an inconsequential one-off joke that was quickly abandoned. the era of games it's meant to skewer is, more or less, over by now. the joke's not very funny anymore, if it ever was. Ian Bogost's "Cow Clicker" sort of did another version of that anyway.

networks of wealthy indie and ex-industry figures who popped up in the wake of the indie games boom i.e. The Indie Fund which chose projects and entrepreneurial new personalities to elevate based via whispery connections of private mailing lists and secret forums and reflected the interests of influential people in the space, were once incredibly important. the tech industry broadly never really got behind funding the game

industry outside of whenever it needed to drum up a wave of hype around

some new tech i.e. in the big VR push of the mid to late 2010's or the great NFT and AI debacles of the past couple years. so the funding was usually left towards other sources.

so now things in the space have given way to one increasingly dominated by indie publishers and acquisitions by larger companies, which are both basically replicating what happened to the game industry in the 90's. the same sort of creativity-stifling forces all those early indies were fighting against in the 00's are back in a different form. and there has been an increasing amount of discontent with the shoddy deals many of indie publishers are reportedly giving indie developers as well. so this totalizing fantasy of transforming a space forever thru 'Meaningful Play' may still exist in places like games academia, but in the commercial industry they have mostly given away to the hardened faux-wisdom of what i often semi-disparagingly call "The Industry Realist" (a term which i think i borrowed from Emilie Reed).

=========================

|

| from Uin by Matt Aldridge (aka biggt) |

in some ways it would be easy to believe you could wash away the depressing legacy of this bygone era and try and attempt to hit the reset button, as many who are uncomfortable with the deeper questions its legacy introduces seem to

want to do.

especially as many notable figures from the era are mired in complaints about workplace abuses (or sexual abuse) or get sucked into more and more arcane, openly

eugenicist, and far-right belief systems i.e. longtermism. even for how filled with odd, fevered egomania and weird intensity as the space could feel at times during that era, i

never could have anticipated events taking some of the strange and

dramatic turns they have in the past ten to fifteen years. nor could i conceive of the heroes and villains (seemingly many more villains than heroes) who have emerged from them. at some level video games are this seemingly inconsequential thing, yet they always seem to somehow perfectly encompass so many different things happening in larger culture and society at once.

but it's important to remember that the utopian "communal, hippie-infused 'gift economy'" side of the tech industry outlined in the Californian ideology piece was and is a driver that has fueled a lot of the indie space, especially in its early days. The Marriage and Passage are both free games presented mostly as experiments directed towards a smaller niche audience, after all. there's a comprehensive tome to be written at some point about the history of influential free games and web games, particularly of the 2000's and early 2010's, and how the commercial indie game boom of the late 00's and 2010's directly came out of that. i would love to see a Our Band Could Be Your Life-style retrospective (i'm an indie rock kid, sue me) on a group of free game makers to finally set the record straight on some of these games and make sure there's broader awareness of them.

doing so would have to adequately grapple with the thorny legacy of many figures from this space, of course. but games like Matt Aldrige's Uin (pictured above) are genuinely hard to find much info on now and seem fairly forgotten, in spite of being only a bit over a decade old. i do appreciate indie game developer Zaratustra cataloging some of these games recently in some posts over on the new social media platform cohost, though.

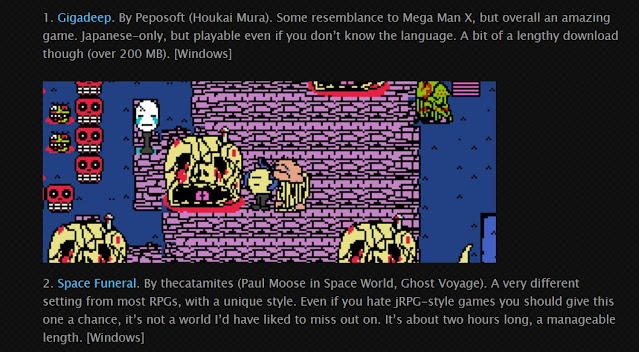

this is important to me partially because: had i not seen the above screencap of Space Funeral by thecatamites (aka Stephen Murphy) from this post on indie game community hub Tigsource by inimitable community figure Paul Eres in 2010 and been instantly compelled, or had i not stumbled upon a handful of memorably strange and unsettling narrative games by increpare (aka Stephen Lavelle) i probably wouldn't have stuck around in this space at all. knowing that there was work that seemed more on my level, both in terms of scope/technical ability and in terms of artistic risk, meant there was something more going on here that i could attach myself to spiritually.

i came back to following games (a space i had previously occupied via various online forums in my youth) after realizing how narrow any potential i had to make it as a filmmaker or musician and needing to find work elsewhere. i was not interested in doing some fuckin' apps, i was interested in art! and you'll put up with a lot of bullshit in order to get to the thing you think you really want.

if you're a young person entering any space like this naively looking for new opportunity, and you're not an Ivy League dropout looking to be the next big entrepreneur, it was extremely hard to articulate or understand all the contradictions that existed there - or why, exactly, you couldn't fit into the space. i just knew that i didn't fit in. when you jump right into the epicenter of a space as it's exploding, of course all the people with dollar signs in their eyes didn't want to talk about some weird free web games you played. why would they? that stuff didn't even exist in the same universe, to them.

but i didn't fully understand that. so clearly it seemed obvious that

none of this was meant for me. i used to feel like a person out

of time. i just was not very interested in what most people were talking about at all, and felt like i constantly had to speak a different language to be heard. i had unending fantasies about moving to Europe (a thing i

had absolutely no means to do), a place where i thought people really

would understand the true value of art, rather than being forever stuck in the hyper-capitalistic

hellscape of America.

but that wasn't possible, and anyway: you always kind of have to ride on the wave that other people set into motion decades before you showed up in order to get anywhere, regardless of where you are. you have to piece together what you can and hope to find your own way into the world. there is no other real option. sometimes that requires some suspension of disbelief. without it, i'm not sure i could have operated at all. and in spite of feeling very much on my own island in those early years, i later ran into a lot more people who felt the way i did, and struggled in the same way i did.

and it's at some point after meeting about ten different big industry people who inexplicably seemed to want to talk to me when i realized that, rather than being fundamentally at odds with the hyper-libertarian entrepreneurial side, the communal utopian spirit of indie games was constantly in dialogue with that side. one simply could not function without the other. people needed genuine creativity and communal support, but they also needed to pay the bills and get visibility.

i'm not saying this balance was a healthy or stable one at all, though. it was, in fact, always tipped far towards the side of wherever the money and power was at that moment. but the idea of indie games being a romanticized DIY thing was crucial as a selling point for so many of these games at the time, to people with money. the resulting landscape was one that seemed to constantly see-saw between this incredibly utopian communal spirit of expression on one hand and weird cutthroat hyper-individualism with this intense religious devotion to technology on the other hand - in a way where it was often hard to easily pull one apart from the other. there wasn't any real way to escape this constant tension, because it was built so deeply into the framework of the online spaces all of us existed in.

i've often described the whole space to friends who don't follow games as "harboring both absolute genuine eccentric outsider freaks who cannot exist in another space due to being very marginalized and needing it as a form of expression... and also very conservative people who find other forms of culture too free-wheeling and open-minded for them and use games as a way to escape from a world that freaks them out." although distinctions between those two groups aren't always so easily made, and they would often be (and still are) incorrectly lumped together. and within this dynamic, you had socially maladjusted people making bizarre highly personal experiences about depression and identity constantly intermingling with extremely competitive "type A" professional corporate grindset sorts of people. and, of course, incessant thinly-veiled hostility simmering between different groups at all times.

|

| from Kero Blaster |

Cave Story, to me, perfectly embodies this tension between utopian charity-ware forged of passion and personal expression and cold, and cutthroat business entrepreneurship. if you know much about video games, you might have heard of this game. so many things about the image of the solo indie developer started from Daisuke "Pixel" Amaya, its creator: a disillusioned salary-man from Japan who had absolutely no experience in the game industry, yet somehow pulled together everything from his toolbox in his spare time to make his loving tribute to video games: one which inexplicably turned out to be a masterpiece of a scale and scope people hadn't broadly seen before from a game distributed freely. this captured the hearts and minds of people across the world.

and from this springs the myth of the indie game developer (who is probably a guy) who imagines himself as a white collar Mario breaking his corporate chains and reclaiming his humanity

by rescuing the princess, sending the rest of the world hurtling

towards the future. these outsiders were poised to change the fate of the industry. (the design of Cave Story, while not a pure Metroidvania, squares pretty nicely with the forever-obsession with Metroidvania-influenced 2D platformers in indie space, from Seiklus to Hollow Knight, by the way.)

however, in the midst of this feel-good story arrives a villain. there have long been rumors of notable indie game publisher Nicalis (Tyrone Rodriguez) stealing the rights for Cave Story away from Pixel - and that Pixel's next game Kero Blaster was informed by his experiences working with the notorious publisher. the actual nature of the business arrangement between Pixel and Nicalis is not public, though. what is known is Nicalis is reportedly not a very pleasant publisher to work with and has DMCA'ed freeware versions and fan mods of the original Cave Story in the past (though the original freeware version is still available). youtuber TectonicImprov attempted to summarize what is publicly known about this whole story in a video from three years ago and didn't find much concrete info to verify things, so i won't go into it any more here.

Nicalis is also notable for commercially publishing work from many well known freeware developers of this era - from Knytt Stories creator Nifflas (Nicklas Nygren) to VVVVVV creator Terry Cavanagh, to Edmund McMillen of Super Meat Boy/Binding of Isaac fame, and of course, to Pixel. the struggles of these freeware developers, and many like them, popularized and legitimized the free game space. this made it easy for the big companies like Microsoft and Sony to show interest in digitally distributing, and new publishers to spring up and start making serious money off these games. but also, many hit commercial games themselves were made out of free games. Minecraft was famously originally inspired by the idea of being a clone Zach Barth's free game Infiniminer, which he later made open-source after Minecraft came out (the story behind which the youtube channel People Make Games did an excellent video on).

Undertale arrived partially from the online fandom around the wildly popular free web comic series Homestuck, which its developer Toby Fox had provided music for. Undertale and many games of its ilk also very likely could not exist without the long-lasting and intense fandom around Yume Nikki, the mysterious freeware RPG Maker game from 2004 by the equally mysterious Kikiyama, easily one of the most influential free games of all-time. even indie hits of the time like Dear Esther or The Stanley Parable were commercial game adaptations by creators of popular existing fan mods they had made in the Source engine. none of this was secret information - these markets sprung out of spaces centered around free or fan-supported art that were broadly already attracting a lot of attention.

which, of course, is just another reflection of a larger trend in Silicon Valley: an industry absolutely built on top of the free labor of open source developers.

the point i'm making here is that it's not so easy to cleave the utopian, communal side of games that celebrate the passion of creative expression from the cutthroat business landscape filled with whisper networks and rampant exploitation of developers. it's not so easy to cleave the very radical new works in this space that empowered new groups of people to re-imagine how art could be experienced/distributed from the fascist eugenicists who were using their works and status to help remake the entire world into a fully privately-owned self-regulating space governed by technology companies either. any attempt to create a portrait of this space that ignores or reduces any of these complicated tensions is very much papering over the reality, of which there always seems to be a concerted effort in the game industry to do. and that's what makes it so fucking difficult to talk about any of this!

====================================

|

| from Cruelty Squad by Consumer Softproducts |

last year i met up with a successful AAA video game industry person i've always looked up to who has been supportive of me and my work over the years. at some point during the conversation, he said (and i'm paraphrasing) "i enjoy a lot of your observations, but i just don't get where your whole thing for experimental art games comes from. i don't get what's so interesting about that stuff." i fumbled a bit trying to respond to this, mostly because we didn't have a lot of time to talk. but i've thought about it a lot since, particularly in light of some recent developments that i'll talk about at the end of this post.

and i mean, look: i can't tell anyone what to care about at some level. i got into games primarily through some extremely

mainstream stuff, probably like everybody else. my favorite game might be an extremely obscure title known as Super Mario Bros 3. i have spent an inordinate amount of time making videos about levels from Doom wads. i'm not going to turn this whole post into advocating for the overall value of promoting art others might find too boring, caustic, or objectionable either. unless you want to

re-litigate the entire modern history of art and the constant presence of this debate, which i somehow

don't think we're going to be able to resolve here. it sure never fails to be an exhausting conversation to have, though!

but if we do want to make an argument for video games as a serious form of art, or culture, or whatever else... then this conversation still has to be had. particularly when it comes to games made on the margins, which often receive negative attention and very little support, if they receive any at all. especially in the climate of an increasingly intense devaluation of artists and art that is happening across all creative industries lately. video games' proximity to tech, in particular, adds extra intensity to the STEM-addled tech folks who are not exactly literate in art history setting the terms of everything else culturally (and i mean everything). there's a reason why Martin Scorsese is going out there a bunch these days talking about the value of artistic curation over "content" and whatever else. it turns out tech industry people are, broadly, not very friendly to art!

there's just always that classic anti-intellectual standby propagating around that says that people who make art for art's sake must be elitist snobs with trust funds obscuring their not particularly deep insights behind a wall of artsy posturing and tricking people into thinking they're a genius, or one of the many endless variations on this. it's a series of un-evaluated assumptions many people carry with them. and i think those sentiments continue to circulate in the public because: they're easy to believe! it would be so much easier for me to believe it's all this way. it would make things so much simpler! lord knows, there are people who fit most of these categories out there soaking up undeserved acclaim. the indie game scene certainly elevated at least a few.

but my experience around various artistic communities has overwhelmingly shown me that a lot of people who make niche artsy games are very much on the margins of larger culture and have chosen to focus on what they do because it's one of the only ways they have to distinguish themselves as artists. a lot of these games generally don't make any money at all, far from the idea that they some kind of secret shadow funding source. i don't think it's very different in a lot of other spaces outside games, either.

there are some signs that these more unconventional works being fated to ultra niche status is changing somewhat. when the unexpected cult indie hit Cruelty Squad (by Finnish multimedia artist-turned game designer Ville Kallio) caused game industry vet David Jaffe to announce on twitter that he refunded the game and that the positive reviewers on Steam must have been trolling, fans pushed back - inadvertently causing a spike in the game's popularity. and that made me smile a little bit. Jaffe's not exactly a well-liked personality, and Cruelty Squad uses mechanics from popular commercial games in several ways (notably the Thief and Rainbow Six series) but it at least shows that there is an audience out there for broadly very different kinds of work that a lot of game industry vets don't understand.

which, to be more generous here, gets at the expression i've seen other games industry people (who are not David Jaffe) make about this stuff: that people who make artsy niche games are intentionally kneecapping themselves by making inaccessible art that a lot of people won't want to actually experience. inaccessible to whom exactly (vs. AAA games) is always a question that should be asked here. especially when it comes to some of these games like Yume Nikki that have garnered huge audiences. but to many of these industry people, this means the artsy game creators could very likely burn out and give up, instead of sustaining their careers in the space longer-term or helping change the industry for the better... whatever those industry people think that means.

what i really want to express in response to this (and the aforementioned industry person i know's) sentiment, but have struggled to, is that: how do you know that the industry of now is going to look even remotely like what it will twenty or thirty years from now? how many times are people told "this is just the way it is now" about their space of work only to have it completely transform to something almost unrecognizable in a few decades, and then be forced to adjust to that new normal?

professor David Harvey defines neoliberalism as "a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human

well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial

freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by

strong private property rights, free markets and free trade." the

nature of neoliberal capitalism is that any stability or safety net a centralized body

might provide is replaced by an unceasing need for creative destruction via 'innovation'. staying afloat and just existing in a space where an increasing social burden is being left to the free market via private

platforms with interests that broadly don't align with their users means the default expectation placed on basically everyone is to be (to borrow a phrase i like from

David Kanaga from a video presentation we did on neoliberalism)

a speedily transmogrifying entrepreneur of the self. of course the people at the top will probably never change. but everyone else is expendable.

what i'm saying is: how do you know people making some random ass weird art games at little to no cost are always going to be engaging in commercial suicide when compared to the the frankly unsustainable production costs and labor practices behind so many AAA games now? how are the economics behind any of this remotely stable? games analyst Liam Deane in a Game Developer post from only a few months ago said: "almost every trend we see in the games industry today—from the frenzy of studio acquisitions, to the constant search for new revenue streams, to the proliferation of startups offering games tech solutions—can be traced back to the cracks that are growing ever clearer in gaming’s traditional economic model." well-known game industry labor reporter Jason Schrier seemed to echo this evaluation in a piece for Kotaku in 2017, stating that because of the financial volatility of so many game companies: "observers like me worry that the video game industry’s current path is not sustainable."

and in the 'indie' space, there is no way to study the tea leaves of the market and reverse engineer a new world-changing hit like Minecraft, as the endless number of marketing talks about games seem to want to do, either: because an unprecedented freak hit like Minecraft could not reasonably have started out trying to turn into what Minecraft turned into. anyone who thinks they were blessed with the secret to navigating a way thru the seemingly random winds of the market (beyond having lots of money) are profoundly deluding themselves - and, more importantly: deluding others too. i don't want to even go into the sorts of results you find when you google the phrase "indie game marketing", but there are a massive number of sources you can find there claiming to provide advice and consultation on how to market your indie game that either are common sense, or just pure scams.

i continue to operate in a space around things that are seen as hopelessly niche and uncommercial because - that's what i do right now, and what the hell else am i going to do? besides: what the market says (or what metacritic says/doesn't say for that matter) about a given work at any given moment in time has little worth to me in determining the overall lasting artistic value of that work. and that's, to me, what a lot of game industry people who are stuck in a certain framework of thinking about how to operate making games are unable to understand. sure, we all have to survive: but what does survival really mean when what you need to do to achieve it (unless you're one of the lucky ones) is constantly changing?

some might believe that my postulation about a reality where weird art games grow into a mainstream force is overly optimistic. however, i would say that it's in many ways actually the opposite. in some way, a hypothetical industry where everything is infused with the essence of a cryptic art game with quirky visuals and weird mechanics is the opposite of what i want. when everything is up to the winds of the free market, creative destruction of an existing order is the law of the land. radical niches either wither away and die or get absorbed into the mainstream. in the supposed best case of these niches breaking out, broad audiences will eventually get exhausted by them and the cycle will continue on to something else. this happened to grunge and "alternative" music in the 90's, something i am just old enough to have lived through, along with so many other things. even if the absence of that, there's the issue of rapidly changing technology and consumer demands that might enable more creative and interesting work to happen at one point suddenly changing. and then everyone is forced to find cheaper ways of production, and the old methods get left behind (like with what happened to the animation industry from the 90's into the 00's).

both of these things happen constantly at all levels of culture, you just don't always hear about them. it's, again, the nature of capitalism to do this to all art and culture. and all of this just lends an air of disposability and a feeling of trend-riding to potential deeper expression that could spring forth on a longer term basis from these waves. if you want to make a case for the real artistic and historic value of a particular work or group of works, being seen as just another market trend is not a great way to do that. if you want them to be just seen as novel toys or tools to help sell products that cause people escape into an increasingly privatized world of technocracy, then maybe it does.

but i also just recognize my larger powerlessness when it comes to the ability to change any of these forces. there's not a whole lot you can really do, short of changing the entire economic order that we all exist under. and we all know how that's been going lately. but that doesn't mean that just impotently whinging about how it's all hopeless and there's no ethical consumption under capitalism so you should just do whatever the hell you were going to do in the first place is helpful either. i find doomerism fairly useless (while understandable), and as much of a trendy wave of sentiment right now as any other trend.

i'm a queer trans woman and a lot of the people i know working in this space are trans and queer as well. people with power and influence increasingly are declaring a war on all trans and queer people right now in the US and the UK - in addition to the immense struggles trans and queer people face globally. a censorship movement to ban books in schools and libraries, and ban certain kinds of public performances is growing right now as well here in the US. we are firmly within the next wave of Satanic Panic, and the rapid pace that it still is growing in spite of a lack of apparent overall public support is frightening. and that's not to mention anyone who is affected by the overwhelming climate of mass incarceration in this country and the cutting of public funding towards libraries and the arts, or people left permanently ill from the COVID-19 pandemic, or anyone in the space stuck in the middle of a massive global conflict in Ukraine - or many other things.

there is so much at stake here that this space is a part of that go far beyond the cultural status of the medium of video games (what this post is mostly about). even if i don't believe in the current economic system we all are forced to operate under at all, or find it to be sustainable for human life - there is still a great deal of urgency needed here put towards finding a way to help protect and preserve these things somehow.

============================================

the constant tension between video games being seen as a serious form of culture demanding larger celebration and preservation vs. their existence as pieces of creative technology which are there to help kickstart the new fully-privatized technocracy led me, somewhat randomly, to a post by Ernest Adams on Gamasutra (now Game Developer) from 2001. in it, he proposed an idea to adapt the Dogme 95 film-making manifesto into video games, which he called "Dogma 2001." the proposal was based around his own mini manifesto of: "Technology stifles creativity" and the idea was to force designers to focus far less on technology than on design, with the intent of producing less derivative works.

i can't help but laugh a little at this proposal in hindsight, even though i agree with the spirit in which it was started. Dogme 95 seems to mostly exist now as an anecdote to be brought up by curious film students looking for ways to buck the system, yet very little attention is often paid to the work that came out of it (Thomas Vinterberg's Festen is good though). it was also notably abandoned by its creators after several years. this isn't unusual for most manifestos, which can be fun to engage with as a creative challenge or call to action, especially for outsiders (i wrote one in 2015 after all). and there have been some notable ones in video games that deserve historical recognition. but the lasting impact of most manifestos beyond as just an exercise in creative writing on the part of the writer can be hard to measure.

the other reason i can't help but laugh at this attempt to make "Dogme 95, but for games" is the amount of movie envy that perpetually exists in the game industry. there is this desperation of so many who work in the industry to be a part of a consequentially serious form of art, like film, that has this romantic social purchase and the weight of history tied to it. as Chris Crawford said, game developers are very defensive about the sordid reputation of the field they work in. 'Content Creators' fondly reminiscing about a part of Zelda game they played in their youth on their youtube channel for 800k subscribers doesn't have quite the same ring to it as Martin Scorsese writing about how attending Fellini premieres in his youth profoundly changed him as a person. the environment that produced filmmakers like Fellini was shaped by huge upheavals of the social and political order that profoundly changed how film was viewed in broader society. and the fact is: so many of these game industry people who want video games to be a serious, consequential art form are unwilling to commit to what that actually means.

anyway, a year after Adams's attempt to propose Dogma 2001, a bunch of game designer/programmers got together in a barn in Oakland, California for four days in March 2002 and commenced the '0th Indie Game Jam'. the "jam" in "game jam" comes from "jam session", as in a place where jazz musicians riff on a single melody for an extended period of time. the film envy of the Dogma 2001 proposal seems to not be present in what sparked the game jam: instead, it was inspired by a technological puzzle (how many sprites can you reasonably fit on a screen?) which caused designer/programmer Chris Hecker and ex-Looking Glass programmer Sean Barrett to start recruiting others for the game jam. but Hecker later talked to Adams and expressed very similar desires for the need for more innovation in the video game industry. these were both people fighting against the sameyness that increasing technological demands, corporate consolidation, and the unfriendly treatment of devs by game publishers produced by the changes at the end of the 90's.

i do think the use of the word "jam" in "game jam" (a term coined by Chris Hecker) is an interesting choice given the parallels to culture jamming, an anti-consumerist practice meant to disrupt mainstream media culture through various forms of creative protest. especially given that one of the most notable figures in the culture jamming movement is Jacques Servin of the prankster activist duo The Yes Men. Servin was a former employee of (formerly) Bay Area-based Maxis Entertainment, the same company Chris Hecker later worked for as a designer/programmer on Spore. Servin was famously fired for secretly adding a code in the game SimCopter that revealed kissing bikini-clad men on certain dates. this was reportedly done in response to the poor working conditions he dealt with at Maxis.

if any of the designers who started the 0th Indie Game Jam had more radical motives towards culture jamming beyond just increasing experimentation and innovation in the games industry, or they were driven by film envy to emulate the radically stripped down work of Dogme 95, they certainly didn't express it publicly. but the coincidences here are just interesting, and outline how many of these threads continue to exist in parallel to each other.

|

| Jon Blow hosting the 2009 Experimental Gameplay Sessions (also known as the Experimental Gameplay or Experimental Game Workshop) from Us and the Game Industry |

anyway, the results of the 0th Indie Game Jam were shown at a new session called the "Experimental Gameplay Workshop" at the Game Developer's Conference in San Francisco the next week. with Hecker and another participant from the 0th Jam (another ex-Looking Glass programmer Doug Church), along with later EGW host Robin Hunicke... this workshop was co-founded by a guy named Jonathan Blow, who ended up hosting the session for many more years. you may have heard of this guy before. Blow was a programmer who did contracting work around the industry at the time and wrote a tech column for Game Developer Magazine called The Inner Product. he later described his intentions for this column as:

"I set out to write about technical subjects at the edges of professional game developers' understanding (or at least my own personal understanding), and to perform experiments that may be useful to professional programmers but also out-of-the-ordinary enough that people would not have explored those directions themselves"

Blow clearly shared the interest in pushing the boundaries of creativity in the game industry that motivated the 0th Jam (which he participated in). he was clearly using his studies of advanced programming, his industry experience, and his (and his co-founder's) platforms at the EGW to help propagate these ideas.

while it's hard to exactly measure the overall impact of the workshop (sometimes alternately called "The Experimental Gameplay Sessions" or "The Experimental Game Workshop"), it's clear from looking at the games presented in its 2009 iteration (which included big indie names Flower and Spelunky, among others) that it was profoundly tied into the movement of the time happening around indie games.

from his host podium during the 2009 session, Blow actually expresses something about the shift happening in industry at the time that a lot of people in the room are probably thinking, as captured in the documentary Us And The Game Industry:

"this year was a drastic discontinuous change from previous years, and we were kind of hit unexpected. many people have observed that somehow, maybe it's the rise of downloadable games or the easy availability of development tools on the internet. but somehow there's been a little bit of an explosion in creativity the past couple of years. but this is, i think, the most consistent collection of designs that are doing what i'd describe as 'pushing the boundaries' in the most consistently thoughtful ways."

he had a good personal reason to be optimistic about this explosion in creativity he described: his game Braid had just come out in the US for the Xbox 360 the previous year to rapturous reviews, and was just about to be released worldwide for PC a mere month after this session. the large success of Braid would catapault Blow to a mainstream figure in the world of video games, and as someone who received fawning profiles from mainstream publications as a savior of games in larger culture (which exasperated his many detractors around the world of video games).

his talks about game design - like this one on puzzle design done at Indiecade (an indie game-focused festival started in 2005 in LA by many industry figures connected to those who did the 0th Jam, with the idea of it being a Sundance Festival for games) in 2011, are a big impetus for what got me interested in the world of video games in my early twenties. i'd go back and forth with a friend i met on the Tigsource irc channel about game design and about Blow's insights. the same friend actually later sent me money for a new laptop when i was in dire financial straits, a thing that helped me tremendously in this period. a few years later, i spoke at Indiecade... and then GDC. i felt a great deal of goodwill coming from all of this world.

==============================================

|

| from Reventure by Pixelatto |

the new ecosystem produced by the commercial success of indie games like Braid (enabled by digital distribution and new development tools, as Blow mentioned), new festivals like Indiecade, and industry platforms like the EGW eventually coalesced into a very specific trend i call the "One Clever Mechanic (1CM)" school of design. these are games constructed around one central novel design idea, or gimmick. 1CM games usually exist in some kind of fairly normal concept or genre, except provided with a twist. the idea here is depth instead of breadth.

Braid's time manipulation mechanic was the classic example (or Fez's rotational 3D four-way sidescrolling platformer worlds), but there was a far greater amount of those games out there. games like The Unfinished Swan, which was based on revealing aspects of a first-person 3D world via painting them out, or the 2D puzzle platformer Recursed which was structured around recursive worlds, are two random examples of a very large number of these sorts of games. but the example screenshot above is a later game from 2019 called Reventure: a 2D platformer where your objective is to die in as many different ways as possible. i'm putting it here specifically because i like Reventure, for the record... but it also arrived by the time this wave had almost entirely died out, so its audience appears to be a mostly different one from the industry insider crowd of the late 00's.

if i had to pinpoint why so many of these games were produced, i think it goes all the way back to the impetus behind the 0th Indie Game Jam: a surplus of new specialized production techniques which led to a focus on novel, memorable, funny concepts. easily presentable mechanical gimmicks had potential to become an excellent selling point for indies looking to readily distinguish themselves and stand out from the bloated AAA games of the time and also show off their design prowess to the industry at large. of course, many indie games during this period didn't necessarily have an 1CM-style approach. but the 1CM formula became an easy shorthand pitch especially for developers moving from the industry space and into indie (especially unproven ones who didn't have the longstanding reputation of flash game developers like Edmund McMillen) to stand out and attract interest.

so 1CM's tended to proliferate in the commercial indie space, where attracting the interest of platform holders and industry folks was the key to getting in. and once you were in, you could lay claim to a small subset of the space that no one had explored in as much depth as you. you were doing something one-of-a-kind. you were planting your flag on a new piece of fertile ground. you were the empowered wandering nomad exploring the digital frontier, unlocking new possibility for the rest of the world to prosper from.

the rest who were not able to break through to taste the fruits of this new supposed wild west of game design were probably in the free indie game space - the one which produced games like Uin or Space Funeral that i mentioned above. this space was far more chaotic and hard to summarize, but often included games that didn't look as respectable or professional to industry platform holders or didn't as easily communicate what was unique or interesting about them design-wise to outside observers. the lack of ex-AAA professional industry people (who were attracted to commercial indie in large numbers) is part of why there was a bias against this less respectable-seeming space. many older industry people had not grown up in internet communities, so didn't understand these new online natives. because of this bias, the split between commercial and free indies became more pronounced in the early 2010's, and it was embodied by websites like the short-lived but influential Free Indie Games and then the also short-lived but influential "altgames" movement which proudly stood in opposition to the big commercial indies.

this is where i (and this blog) entered the picture. there was a real ideological divide forming, which i would describe at the time as the professional hyper-capitalist boys club vs. the unprofessional freaky outsiders. the first camp attracted a lot of people coming from industry contexts, and the second camp tended to be online community natives with less resources who generally skewed younger. i ended up very much in the latter camp. my game Problem Attic from 2013 came partly out of a desire to explode the tropes of the 1CM-type game into absolute absurdity and terror. if you were in the latter camp like me, this meant an increasing suspicion with anything to do with "indie" or the industry at large and with the way so many of these figures in this scene pulled up the ladder behind them once they became financially successful, far from the utopian promise of community many had espoused earlier.

as the differing visions of what games could be in the freaky outsider camp mostly failed to materialize in any kind of mainstream way, and as the reactionary movement of gamergate grew like a cancer onto the scene... it led to a huge fracturing of groups. later on, itch.io arrived and Steam became a semi-open platform, officially killing the free vs. commercial divide as a matter of unprofessional vs. professional. but the mainstream indie space (which i'd also heard referred to as "the Indiestry" or "AA" games) was already becoming increasingly formulaic.

the same year at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop that Jon Blow announced: "this is... the most consistent collection of designs that are doing what i'd describe as 'pushing the boundaries' in the most consistently thoughtful ways", former EGW alum Keita Takahashi, whose well-known game Katamari Damacy had been shown in 2004 at this session, which helped popularize the game towards getting a release in the west, seemed to feel that something was amiss.

in this translated 2009 interview, he expressed dissatisfaction with the EGW and the direction this part of the industry was moving in:

"GDC has grown too big to be what it once was. I honestly cannot stand those sessions that are all about the keys to sales success, the keys to not making a game that fails in the marketplace. I haven't attended all of them, so I might be wrong about this, but I presented on Katamari for the Experimental Game Workshop, and it seems to me that every year the games in that booth just get worse and worse. It is called 'experimental' but the content is just not creative at all. It limits itself to a single gimmick. The presentations are aimed at getting people to laugh and that is pretty much all there is to it. This year it was particularly painful. I didn't think it was experimental at all."

what Takahashi views as truly experimental is anybody's guess. but i privately heard variations of the same critique he made expressed by several other established indie game designers in the ensuing decade after he made them. i expressed them, myself, on this very blog.

the way the indie space was prepping itself for primetime meant shaving off its own edges in an increasingly merciless manner in order to achieve correct respectability and palatability to the mainstream. if this sounds really at odds with the often highly personal source of inspiration Blow described games from the indie space as coming from, that's because it was. but it felt that whenever this crowd was hit with anything too weird and freaky for them that took this personal game mantra too seriously, they instantly would launch into "finish your game please" mode and hit people with treatises on the importance of polish.

your apparent lack of respectability as an outsider game developer was treated as a threat which endangered their long-term investment in this space - like a father lashing out at his children. you were looked down upon as an unserious joke for not following more conventional industry approaches and modes of presentation. but hey, if you play by the rules maybe one day you'll be called the great new auteur of the space by some journalist from The Atlantic who is hopelessly clueless to the world of games.

|

| Chip's Challenge by Epyx |

all of this made you wonder what, exactly, of substance was left behind the bombast about personal game-making a lot of the time. what was this all even about in the first place (beyond an exercise in egomania on the part of some people)? what great dreams were lurking at the heart of all these respectably rounded-out quirky little mechanics?

i can't see what's inside other people's hearts. but i tend think 1CM exists, at least implicitly, in response to an older design trend i'll call "Anarchic Maximalism (ⒶM)", which was dominant in many 90's and late 80's games i played as a child.

i would describe ⒶM games as great big pile of ideas that, at times, seemingly subvert or contradict each other. novelty and constant surprise is the main appeal here. Super Mario Bros 3, from 1988 (released in 1990 in the US and 1991 in Europe) seems to embody the idea of Mario as the ur-2D platformer, while also subverting the tropes Nintendo had established in previous Mario games. the idea of Mario is turned on its head in many different creative and absurd ways. SMB3 assaults you with novelty and silly ideas from the very beginning, and never lets up.

a lot of games followed which featured designers attempting to show off their chops in a similar fashion to SMB3's huge weird pile of levels, to varying degrees of success. Wolfenstein 3D, a personal obsession of mine (if you've read this blog before), contains so many different ideas and approaches to the designs of its levels in its six episodes that are seemingly scrapped entirely or subverted throughout its short development time. so much so that it can be actually hard to figure out where the real core of the game is at. Myst has a far more focused story, but contains a world which requires constant huge jumps between different forms of puzzle-solving that all must be correctly completed in order to proceed and understand bits of larger story about the world you're stuck in. there's an almost collage-like quality to trying to engage with Myst, and the genre of interactive puzzle games it inspired followed that often less successfully. (this style was derived from older PC adventure games and would, of course, eventually coalesce into the escape room).

maybe my favorite example of ⒶM-style design i recently discovered is the classic Windows 3.x (originally Atari Lynx) game Chip's Challenge, a simple top-down 2D puzzle game. each stage in Chip's Challenge tends to feature new combinations of rules, items, and environments... and the dynamics and difficulty of each stage can vary pretty dramatically from one to another.

i had a lot of fun playing Chip's Challenge for the first time a few years ago, personally, because of how much it reminded me of a type of puzzle game that doesn't get made so much anymore. this outlines my point that this design style has little to do with the hugely scoped maximalism of contemporary AAA, and more to do with this completely feverish devotion to a variety of ideas explored in a scattershot manner. it sometimes leaves these games feeling like a wacky carnival of novelty and game tropes that has no real core, rather than variations on themes that were given more time to develop. video games hadn't become fully sentient and capable of interrogating themselves at this point.

i actually talked about this in my piece on Thief: The Dark Project from 2018, a classic game which i think both really subverts and embodies these tropes and games of the era in general in interesting ways. this all comes full-circle here, too, given the direct Looking Glass lineage into indie game jams and the EGW.

i can imagine this wacky carnival ⒶM approach felt painfully arbitrary and embarrassing to many people who entered into the game industry in the 90's and early 00's. especially as this sort of approach still seemed to keep rolling on into big floppy mainstream games of the 00's like Half-Life 2 or Resident Evil 4, both games with troubled developments that feel like wacky carnival rides that are barely holding together at the seams. but this trend was also starting to die out.

in the earlier days, the process was less focused in a specific direction and more filled with developers who were just quickly trying a bunch of different ideas out. as technological demands and budgets increased, it became harder for game developers to pull together games by the seat of their pants like this without those games becoming giant disasters. more focus was required in all aspects of production.

the production of AAA games had to become more standardized and hyper-specialized, a sort of video game Fordism. this is the approach that defines a modern open-world Bethesda or Rockstar game. they are small wonders of the world, worked on by many different tiny hyper-specialized hands. but that joy of these earlier anarchic games often feels seeped out of them. but, alas, the ⒶM era was basically dead. this psuedo-Fordist mode has become the dominant mode of AAA game production ever since (even as cracks have been developing). which opened the door for programmers like Jon Blow to sell themselves as specialists as in the increasingly specialized assembly line.

and so to me this hyper-specialization means a stark change happened between the ⒶM era and the 1CM era of design. this particularly can be observed in the realm of puzzle games, one of the most purely designery genres. games like Jon Blow's The Witness or Stephen Lavelle's Stephen's Sausage Roll (a personal favorite), two extra chunky commercial puzzle games from 2016, take 1CM-style design and explore every single possible iteration that idea introduces in extreme depth. the wacky carnival ride is gone and replaced by a different kind of straight-faced absurdity that asks you to patiently commit your time to this particular space. these are games about applying a Zen-like focus onto one very specific practice.

this meditative approach, while not necessarily broadly mainstream, seems to have mostly continued on in puzzle design spaces like the "Thinky Games" community.

|

| Yume Nikki by Kikiyama |

so if ⒶM design is a product of a different era, the pseudo-Fordist model is dominant in AAA, and 1CM design is mostly dead in the indie space... what has now replaced it?

in comes what i'll call "Vibes-Based (V✨B)" design. V✨B design tends to focus more on the visuals, story, and music and have a lighter sprinkling (hence the ✨) of game mechanics throughout. the innovation here is not necessarily in any particularly traceable part of the design, but in the novelty of the aesthetics and general vibe of the experience. games tend to be focused more on the exploration of space or a story. they might occupy a variety of different genres or look quite different from each other, but the focus on the aesthetic presentation and the mechanic of exploration is a crucial part.

the free indie games Space Funeral and Uin i mentioned above are examples of this in some ways. but the premiere V✨B game to me is the cult classic exploration game Yume Nikki, which has sustained a massive fan community around it. although this trend originates further back to oddities like famous Japanese-only PSX exploration game LSD: Dream Emulator or the very obscure Go To Hell for the ZX Spectrum.

most of those examples are surreal, strange games with counter-cultural connotations to them. but the V✨B approach has spread all over the map to games of much different moods, goals, and budgets. contemporary indie titles like A Short Hike, Umurangi Generation, and Sable are all games i'd put here in spite of all being quite different from each other in intention. same with the large variety of the twee colorful indie games with often with flat-shaded, low-poly colorful aesthetics or many of the PSX-inspired lo-fi horror games.

not all games with those modes of presentation fit into this trend and many might have different mechanics or tones from each other. they might be more explicitly attempts at remakes of games in older genres, also. but the exploration of space and the vibe of their aesthetic presentation has become a primary focus to distinguish them from the games of old. rather than industry vets or game academics, youtubers like ThorHighHeels are the personalities i associate most with a V✨B lens on game design - which focuses more on specific feelings and details of an experience over a deeper analysis of systems.

i feel the influx of games of this type have sprung out more from dedicated online fandoms than the longing of hyper-specialized professionals of before. the indie explosion led to digital platforms offloading their curation onto the whims of their userbases. this is consistent with the libertarian approach of the tech industry - leaving curatorial duties to the actions of mysterious algorithms. the role of streamers and youtubers has become increasingly important as well. this group, as such, is far less focused on breaking thru industry centers by catching the ear of a professional about your great new game concept and far more focused on establishing audiences you might attain through various means online. often this means spending a lot of time trying to figure out how to 'game the algorithm' in various ways to squeeze any bit of visibility out of it you can. how well the value of your a game translates in a screenshot and short video to a potential new audience is crucial in all of this.

the pushback against some industry figures like Jon Blow means it's clear that a lot of audiences are less interested now in being introduced to obscure mechanics and clever gimmicks that they feel condescended to by the high and mighty game designer. unless you're existing within a well-established genre, which have maintained a steady appeal (i.e. Metroidvanias, deck building games, visual novels, roguelites, etc) it's better to not rock the boat too much and risk alienating people who don't get what they expect. as a result, there is more of an ambient interest in just occupying worlds that are going to provide a reasonably pleasant experience that doesn't demand too much from its players.

the ambient expectations placed on developers for the amount of visual polish for any given commercial indie game is supposed to have is now also much, much higher than they were in the early indie boom. instead of ex-industry programmers who were inspired by the simplicity of 80's games, i now see more comic artists and animators influenced by the art of 90's and early 00's games leading these projects.

a greater amount of manpower is demanded to make many of these games, which means an increase in new developers starting small 'indie' studios or providing various forms of contracting work to those indie studios. many of these new developers, instead of ex-industry vets, are young graduates of an increasing number of game design programs that have sprung up. some of the bigger-name programs were even started in the past decade or so by the same figures from the first indie wave that produced the 0th Jam and Indiecade. all of these young people coming into the space are increasingly looking towards publishers to fund their new small studios.

the look has become so important in the commercial indie space that it has arguably overtaken everything else. some aspects of the presentation have a tendency to be given far greater consideration than many mechanical aspects of a game, depending on what kind of game it is. the look, after all, is what you're selling your game on. this means that games in this style can sometimes lack coherence, just feel underdeveloped - or, at worst, totally frictionless and paper-thin and like an uninspired clone - beyond their attractive aesthetics. you could also say that the long-time consumer fixation on a game's graphics is still here, just in a more trendy #aesthetic image blog form (which, hey, i had one of those so no hate there) rather than an obsession with graphical fidelity.

the unprofessional vs. professional indie developer divide still exists here too. instead of non-commercial vs. commercial (because digital platforms now make selling games far easier for anyone), a related divide has formed. developers made up of one, two, or three people are often more likely to be making games in an idiosyncratic and personal mode, more akin to older indie programmer-designers. however, unlike those older indies who often espoused the virtue of polishing yourself up for primetime, these developers actually are taking the idea of personal game-making to its logical conclusion - continuing on from the altgame and Free Indie Games era.

but these developers are in tension with the developers who are trying to start small indie studios in order to make higher production value games so they can procure funding from publishers. at their highest levels (which most of these studios do not reach), these indie studios are more akin to older mid-level development studios who mostly all died out or were bought out and merged into bigger companies by the 2010's - and were certainly not considered "indie" by any means. the focus for these studios on a certain kind of industry status and respectability, and the way many of these games subscribe to a more traditional industry school of polish and marketing is more akin to the older commercial indies, however.

| |||

| from 10 Beautiful Postcards by thecatamites & crew |

Toronto media scholar/associate professor Felan Parker examines this new type of mid-level studio that derived from the indie scene in a chapter titled "Boutique Indie: Annapurna Interactive and Contemporary Independent Game Development" available to read here from his book Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques and Politics. at end of the chapter, he offers a warning about the dangers of the prominence of these indie studios pushing out smaller developers:

"This growing middle category... takes up considerable cultural space. Even as it expands mainstream conceptions of what is possible in games, it simultaneously pushes less well-financed and/or more radically experimental game-makers and game-making practices that lack the backing of powerful intermediaries further to the margins"

this side of the indie market, to the degree that it exists in contrast to anything else at this point, is looking more and more just like something out of the game industry of the 90's. increasing professionalization happening in the space around these small indie studios has led to my own use of terms like "portfolio-core" and "prestige-'em up" to describe the more awkward and less successful versions of these games (along with the old standbys of "AA", "Triple-I", and "Indiestry" which get used for the bigger visibility ones).

i adopted some of these terms from some posts made couple of years ago on a private forum about this trend of game by Stephen Murphy aka thecatamites. Stephen developed the classic free game Space Funeral, the game which inspired me from its screenshot in my early days, and the above 10 Beautiful Postcards among many other games. i still think about what he said here a lot (reposted with permission):

"kind of fascinated with the distinct look of a lot of those prestige things. in my head i think of them as representing 'portfolioisation' where the job of artists is just to create individual portfolio entries for aspiring content monopolists to use for leverage in the baroque hypothetical struggle to become the new netflix. in the same way that a portfolio piece is maybe less meant to act as a work in itself than to indicate a more general sense of potential still to be embodied. and that same sense of potential is maybe more appealing to people who already have more money than god than any specific set of aesthetic qualities or sales figures.

what are the aesthetics of potential? clean lines, soft colours, 'warmth', cosiness mixed with purpose, kind of like those mocked up images of new development sites with little nondescript and welcoming people strolling in the sun in the proposed new shopping district or what have you."

because of the influx of these kinds of games, it's not hard to find many that appear to have a large amount of work or visual polish put into them that nonetheless seem to lack that much of engagement or interest from audiences, given all the effort. this was sometimes true in the earlier days of commercial indie, of course. but the number of games being sold wasn't so large, and the modes of production of these games hadn't become so standardized.

after a reasonable amount of attention and press hype put towards the trend of Wholesome Games in 2020 and 2021, for example, a look at the organization's youtube channel at the time of writing shows that only a small handful of game trailers on their channel have cracked 10k views, with many below even 1k. while many of these are likely to be reposts of trailers uploaded elsewhere (as is what often happens with games at this level)... it's still not a great testament to the overall visibility that many of these games which are trying to reach a bigger market have.

recent commercial retro FPS-styled "boomer shooter" games (another new wave that has received tons of hype) seem to be faring a little better due to fitting in better with more traditional AAA game audiences. but, as someone who was interested in early entries in the genre like DUSK and AMID EVIL, increasing numbers of new games in the genre have a look and feel to them that i would characterize as being a bit formulaic and hard to tell apart from each other - in the same way a lot of those colorful Wholesome Games do for me. in addition, many fan lists you can find online of these games tend to blend them in with very well-known older (and some recent) big-name FPS and FPS-adjacent games that inspired the recent wave. perhaps this is for consumers who are new to all of these games, (or creators trying to put themselves in the lineage of those works). but this kind of blending together in the public consciousness of those games with much different contexts and amount of resources behind them is a bit confusing. it could potentially end up really hurting the visibility of the new games in this genre made by smaller developers with less resources in the long run.

later in the aforementioned forum thread, Stephen added thoughts on his frustrations for the increasing pressures for 'non-professional' and freeware game developers like him to join waves of indies like the ones described above and commercialize their work:

"small gamedev discords full of people urging others to commercialise their work by framing that as essentially an act of self care (value yourself <3 you’re worth it! you deserve it!). what could pawsibly go wrong

like ofc goodwill towards anyone trying to get money for their art but it’s weird to me how verboten it feels sometimes to even acknowledge that doing so can be unpleasant. like, it’s a grind! it’s extra work. being productive and hitting a schedule and self promoting and doing all the little babyproofing features implicit in making work for a paying customer rather than just for a curious human being. but it somehow feels base and churlish to complain about this stuff when it gives you access to money (not actual money, just ‘access’, sorry). and i guess a lot of it has already been invisiblised as neutral best practice to the extent that even freeware developers are supposed to feel obliged to do this stuff on its own accord...